Could Claude Code Work for ChinaTalk?

"a few words of instruction, repaid with thousands of lines of code"

Jordan, Jasmine Sun (of jasmi.news) and Nathan Lambert (of Interconnects) talk about their Claude Code adventures on the latest episode of Overfit. Check it out in your favorite podcast app or find it in the ChinaTalk feed!

Claude Code is a coding tool by Anthropic that uses natural-language prompts to create remarkably workable computer programs. In practice, just by opening your computer’s terminal and typing in “claude” and telling it what to do in plain English, it can code, organize and edit local files, build apps, and conduct internet-based research.

Anthropic’s focus on coding agents means that Claude Code is incredibly popular among software developers. It’s also let non-technical people vibecode our way into programming.

After a morning spent watching Claude write Python code for my graphs (in this article), I had an idea: would Claude Code be any good as a China analyst? In theory, the chatbot format is perfect for work that’s both qualitative and quantitative — the exact kind of mixed intellectual tasks a policy analyst or data-oriented journalist might perform.

Putting it through a “China test” of sorts was a fascinating experience, featuring:

Claude has a thing for Falun Gong newspapers;

Propaganda vigilantism;

A discourse analysis breakthrough;

And surprising fluency in Chinese internet slang!

We began with elite politics. Can Claude read Communist Party tea leaves?

Politburo member Ma Xingrui 马兴瑞 has been in the rumor mill lately. In July 2025, he was removed as Xinjiang Party Secretary. Since then, he has been absent from a slew of important meetings, igniting all sorts of speculation. I asked Claude Code to give me three plausible explanations for why Ma’s activities have been scrutinized and what this tells us about Chinese elite politics, using all the information it is able to access.

Claude told me that it conducted two searches of the internet: “Ma Xingrui CCP Standing Committee scrutiny 2025 2026”, and “Ma Xingrui Xinjiang Vice Premier news 2025”. I replicated these two searches in Google in an incognito browser window, and then cross-referenced Google’s top links with the sources Claude cited in its output. There was significant overlap; Claude mostly relied on Page 1 of Google.

The problem was what those links were. Claude’s top-2 sources for its Ma Xingrui report came from Vision Times, a Falun Gong-affiliated newspaper. Opinions about the religious movement aside, Vision Times is not an especially respectable news source: its front page includes such gems as “Unexplained Fatigue May Signal Energy Drain, Not Physical Illness” and “NASA Captures a Dazzling Photograph of the Heavenly Kingdom”. Citing Vision Times’ reports, Claude Code theorized that “interrogations of fallen military leaders have exposed a web of relationships that implicate civilian officials like Ma—possibly involving informal political understandings that Xi Jinping’s security apparatus views as threatening.” Doubling down on this PLA-connected theory, it concluded: “What began focused on PLA Rocket Force and equipment procurement has spread to civilian officials with defense-industrial backgrounds. This suggests either genuine systemic corruption across the military-industrial complex or that Xi is using anti-corruption to restructure relationships between the Party, military, and defense industries.”

Ma might very well have connections to the PLA’s leadership, as Claude claims, but his own career has been strictly civilian. While we cannot rule out the possibility that he was an associated casualty of the PLA purges, there is little justification for over-indexing on that theory as Claude does. In addition, Claude played fast and loose with facts. Its output claimed that Ma’s Xi-loyalist credentials stem in part from being a “Shandong native,” with connections to First Lady Peng Liyuan’s hometown of Yuncheng 郓城 in Shandong province. In reality, while Ma’s paternal grandfather was from Yuncheng, Ma himself was born and raised in Heilongjiang Province and educated largely in the Northeast; the fellow-Shandonger connection is tenuous at best.

To its credit, Claude also cited the good folks over at Trivium China and Bloomberg for factual information, but overall, I’d rate the quality of this analysis as “college student confused by their first Chinese politics class.”

I was surprised by Claude’s apparent naiveté and wanted to test its taste. Can it tell when a Chinese source is reputable, interesting enough, or designed for virality with no real significance? Does a coding agent approach qualitative problems differently? To test this, I gave Claude Code three Chinese articles. For each one, I asked it to (1) summarize the content, (2) contextualize the piece, and (3) examine its significance.

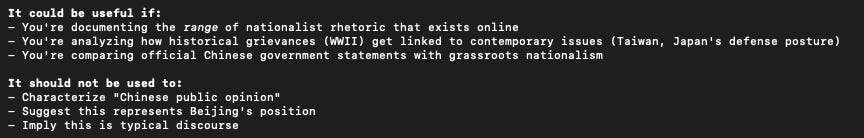

The first article was an unsophisticated screed threatening to “blow off” Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s head in response to her describing a potential Taiwan Strait crisis as “existential” for Japan last year; typical ultranationalist dreck.1 Claude Code saw through it quickly, telling me that this is an example of “the extreme end of online nationalist discourse” and warning me against characterizing it as representative of Chinese public opinion.

This was decently thoughtful work, though if I were actually writing on the topic, I’d add that violently nationalistic rhetoric has been on the rise in China’s cyberspace over the past decade. The state’s management of populist anti-Japanese sentiments is a complex affair, but on the internet, Beijing implicitly sanctions the existence of extremism by not cracking down on such content. It’s a little bit more nuanced than “official statements are different from grassroots nationalism,” but Claude wasn’t far off.

Next, I tried a blog post celebrating China’s decision not to permit the import of H200 chips. Claude told me this was a “propaganda narrative piece” whose framing of “China didn’t need them anyway” represents a classic face-saving narrative by the Communist Party. I wouldn’t go so far as to accuse a blogger with 0 likes of being a direct state propagandist, but perhaps Claude Code is more vigilant. Except it also thinks the entire thing is fake. Per Claude Code, “The H200 customs rejection story would be major news, but I’m not aware of verified reporting on this specific incident.” Sorry, Claude, but this really happened.

Lastly, I prompted Claude to examine this article analyzing DOGE, which is part of a series on US affairs by Tsinghua University’s Center for International Security and Strategy. It’s a well-researched piece published on a respected think tank’s website, with one catch: it was written by an undergraduate student at Sichuan University. Youth is no reason to discount achievement, of course, but it would be remiss of a China analyst to pass this off as very serious Chinese discourse regarding Trump 2.0. Claude Code caught on to this quickly, reminding me that “[student] authorship means less institutional authority than senior CISS fellows”. It decided that the author’s conclusions regarding DOGE were legitimate and that she used reasonable analytical lenses “not unique to Chinese observers.” But it also made sure to remind me that “[the] critical framing of US governance, while measured, aligns with broader Chinese narratives about American decline.” Anthropic’s reputation as China-hawk AI is not unearned after all, I suppose.

Next, I moved on to something more quantitative. Here at ChinaTalk, we write frequently about Chinese reactions to news events and technological developments. We search for thoughtful commentaries representing diverse viewpoints on the Chinese internet, extract sections, and translate and annotate them. (For instance, last month I covered how China reacted to the Trump administration’s decision to sell H200 GPUs to China.) This method is sufficient for understanding the viewpoints of analysts and policy elites, but the vast labyrinth that is online public opinion is often too disorganized to discuss in an effective manner. Trying to capture what Chinese netizens think without big-data tools will always be a cherry-picking endeavor.

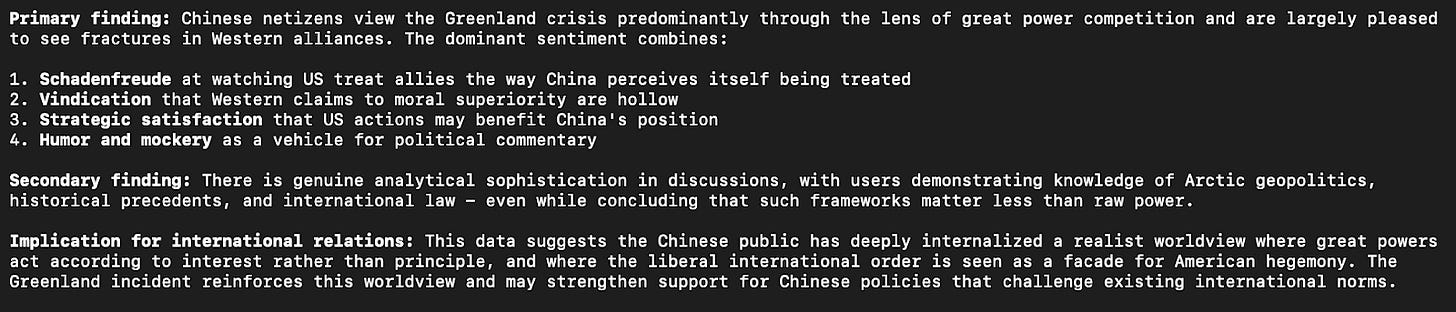

With the help of GitHub and Claude Code, I had an MCP server running in under 30 minutes to do what I’ve always dreamed of: search the entirety of Xiaohongshu/Rednote, export the data, and analyze.2 I was thrilled. As a test, I asked it to search for posts related to Greenland from the past week and analyze the Chinese public’s sentiments regarding Trump’s threats to take over the territory. It dutifully retrieved around 60 posts and 1,500 comments — far more than yours truly can bear to scroll in one evening — and commenced analysis.

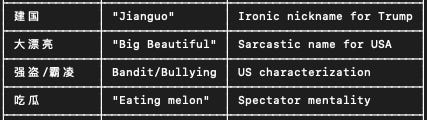

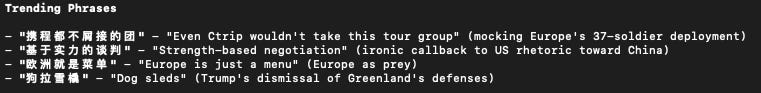

It is here that Claude Code really shines. Its understanding of internet slang was impressive:

It had an eye for catchiness and identified some spicy phrases:

And its takeaways were genuinely interesting! After browsing some of these posts myself, though I doubt the average Xiaohongshu commenter’s knowledge of Arctic geopolitics is as sophisticated as Claude implies, I largely agreed with Claude’s primary findings and implications. Solid university-level work!

Clean text data and a simple Python script: this was a task that employed capabilities LLMs are already great at, and Claude Code’s user-friendly interface made the experience very enjoyable. It lives in your Terminal, writes the files, and runs the code; all you have to do is keep giving it permission to install packages and access websites. That being said, close supervision of the process was important for research accuracy. On my first attempt at prompting Claude Code to perform a sentiment analysis of these posts and comments, it tried to skim on compute by only analyzing comments on the most-liked post, rather than on all posts.

I leave you, then, with Claude Code’s own report about how China is reacting to Claude Code, after searching through posts on Xiaohongshu:

Chinese internet users on Xiaohongshu are reacting to Claude Code with a mixture of genuine enthusiasm and practical cost-consciousness. The most popular posts showcase impressive real-world applications—one viral post (77 likes, 69 saves) describes a user who wrote an automated H1B visa appointment monitoring script using Claude Code, letting the AI “negotiate” with other models like Codex and Gemini to solve problems while they went for a run. Users frequently anthropomorphize the tool, treating it as a “打工人” (worker/employee), with one poetic title reading “几字之恩,千行为报” (a few words of instruction, repaid with thousands of lines of code). The comment sections reveal technically sophisticated users who are eager to learn implementation details—questions like “how did you handle Cloudflare?” and “how do you let Claude Code communicate with Gemini?” indicate a community actively pushing the boundaries of what’s possible. There’s also notable criticism of paid Claude Code courses, with users pointing out that Anthropic’s official “Claude Code in Action” course is free while others charge significant fees.

However, access barriers and cost concerns remain significant pain points for Chinese users. Multiple discussion threads center on subscription pricing—users debate whether ZenMux’s third-party plans offering “5 hours, 20 Opus prompts” are worth the cost, with one commenter noting “还是有点贵” (still a bit expensive) and another asking about account sharing to split the $100/month fee. The comment “封号,根本无法使用” (account banned, completely unable to use) under a token-saving tips post hints at the access difficulties Chinese users face with Anthropic’s services. Technical content about reducing token consumption (one detailed post explains how Tool Search can cut MCP context bloat by 46.9%) gets strong engagement, suggesting users are actively seeking ways to maximize value from limited access. The community appears to be a mix of mainland Chinese developers finding workarounds through third-party services and overseas Chinese users (many posts come from Hong Kong and the US) who have direct access—creating an information-sharing ecosystem where those with access help others navigate the tool’s capabilities and limitations.

We have different definitions of “viral,” evidently, but that’s okay. Some final observations:

Claude has access to all the data in the world, but needs to be told where to look. When prompted to analyze issues without guidance, it leans on the most easily-accessible sources, which are not always ideal. When prompted to look closely, however, it is able to analyze source materials with some critical nuance.

From the Ma Xingrui experiment and a few other news-related prompt experiments, I noticed that paywalls seem to be an important part of why Claude kept getting things wrong. With many reputable sources blocked, its internet browsing drifts towards less savory sites, and it seemingly has no mechanism for selecting sources unless your prompts contain specific instructions.

It does very well when fed clean, structured data. As expected, its ability to generate usable code for simple data extraction and analysis is impressive, and the Terminal experience is genuinely enjoyable.

Its mistakes were mostly factual; I did not encounter cases where it reached erroneous conclusions based on correct facts. Instead, when asked to analyze issues in the abstract, most of the time it simply summarized takes from experts. Without being explicitly fed original data, it was reluctant to develop “takes of its own.” Claude is too over-cautious to be a real policy pundit.

I’m excited to use coding agents to make data about the Chinese internet more accessible. what tools have you been building? We’d love to hear from readers. In the meantime, see you all in the vibe-coding trenches…

I’m not linking to my test articles here because I don’t think drawing attention to them is productive. Get in touch if you want to see the prompts!

This repository, from developer Zouying and an associated volunteer team, worked the best. For those hoping to replicate, I simply pasted the link to this repository into Claude Code and asked it to set it up so that I can search Xiaohongshu’s content. This does require you to have a Xiaohongshu/Rednote account. (Zouying apparently works at Kimi! According to their blog, they developed this tool to automate their personal content production on Xiaohongshu/Rednote.)

Now put this capability in the hands of a government intel analyst (in either country) who does not have nearly the same level of expertise and cultural awareness of anybody at ChinaTalk, and it's not hard to project very bad outcomes. Between "average of averages," janky single-source references, poison fountains, various other deliberate efforts to corrupt data and sourcing, lack of training on the capability, etc. etc., you have a recipe for disaster. That's not a pre-ordained future. It just means education & training (plus human judgment) become more important than ever, along with demanding the same level of analytic rigor people expected in the pre-AI days.

It is not only paywalls, but the robots.txt files on web sites. The web fetch of Claude honors those files, and many sites simply block AI traffic, or Anthropic's traffic, in their robots.txt. This holds for example to main Finnish news sites, including the big one funded by the government.

Among AI bots, Grok seems to be an exception here. Its default harness at X seems not to care about robots.txt at all.