How Much AI Does $1 Get You in China vs America?

And Does the H200 Change Anything?

The AI race between the U.S. and China will be decided in datacenters.

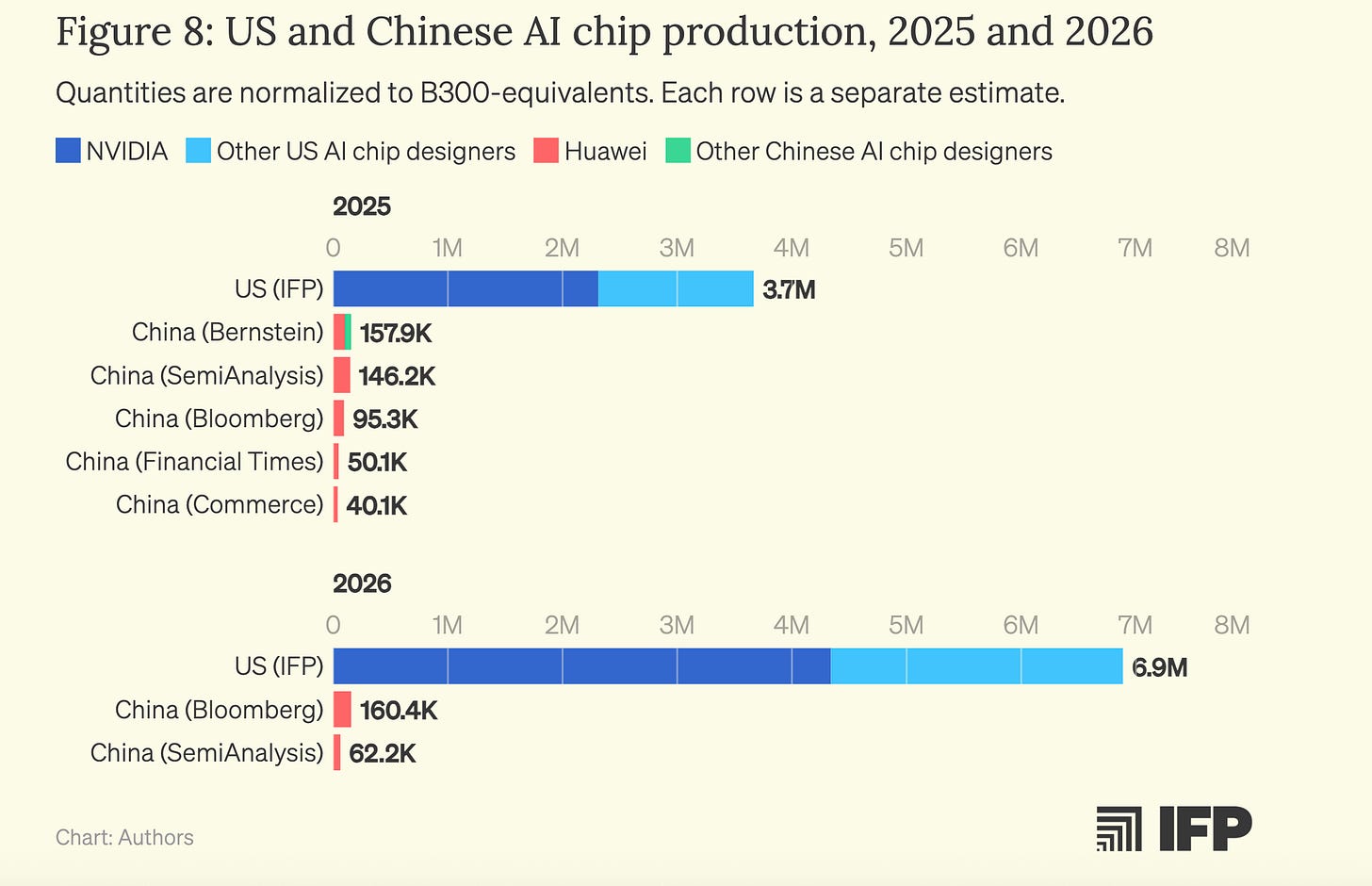

But who has the advantage? Does the recent H200 ban lift change anything? Many pieces relate vague vibes that the U.S. has better semiconductors while China has cheaper electricity, but they lack numbers. This piece tries to estimate how expensive a data center is in the U.S. versus China, and how much “AI” each data center would generate. This piece does not address Chinese access to chips in Malaysia or through smuggling, a phenomenon that potentially increases China’s access to compute drastically.

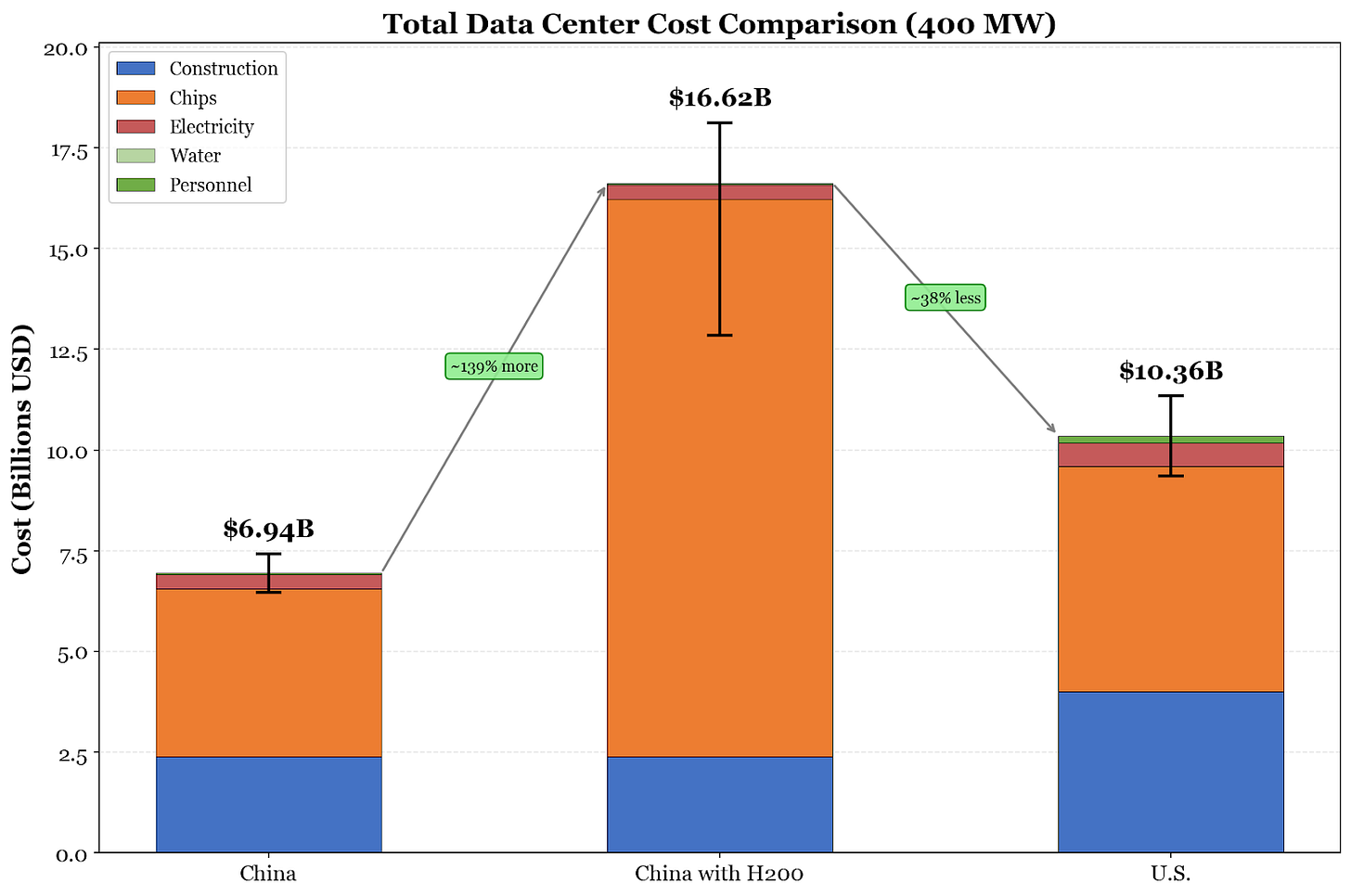

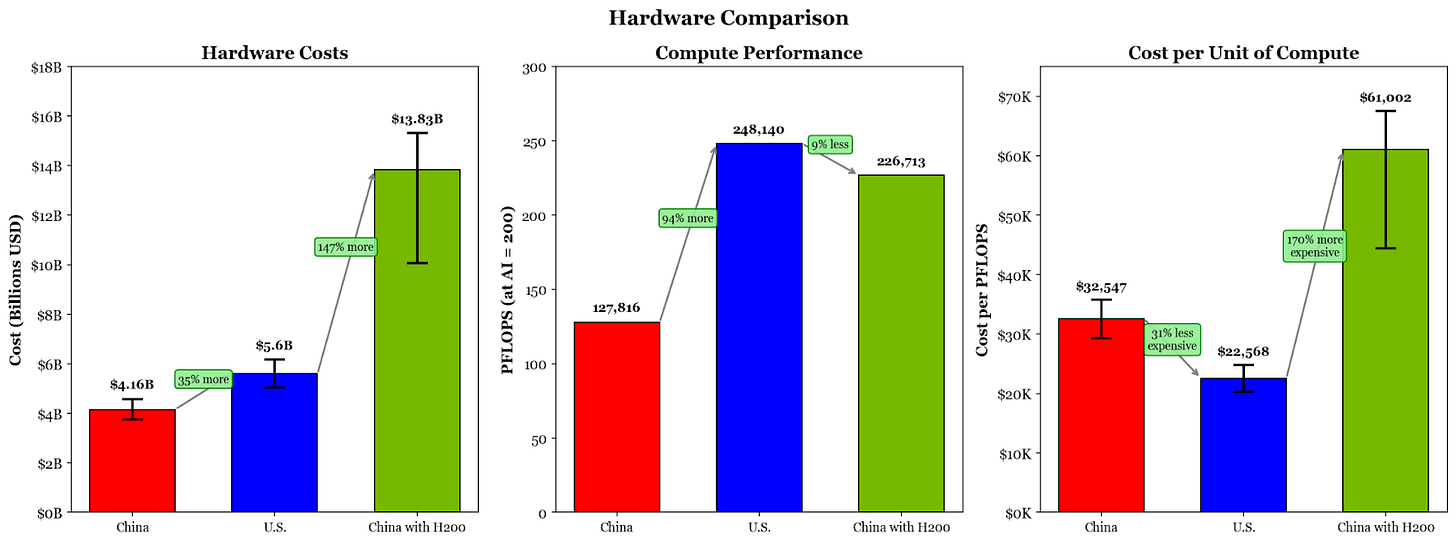

BLUF: The U.S. can build much more cost-efficient data centers compared to China, but unfettered access to the H200 would make the race in raw performance extremely close. Access to the H200 gives China a massive boost considering its domestic hardware production constraints. Lastly, the cost efficiency of these data centers is extremely sensitive to the costs of hardware, which is highly variable and not publicly disclosed.

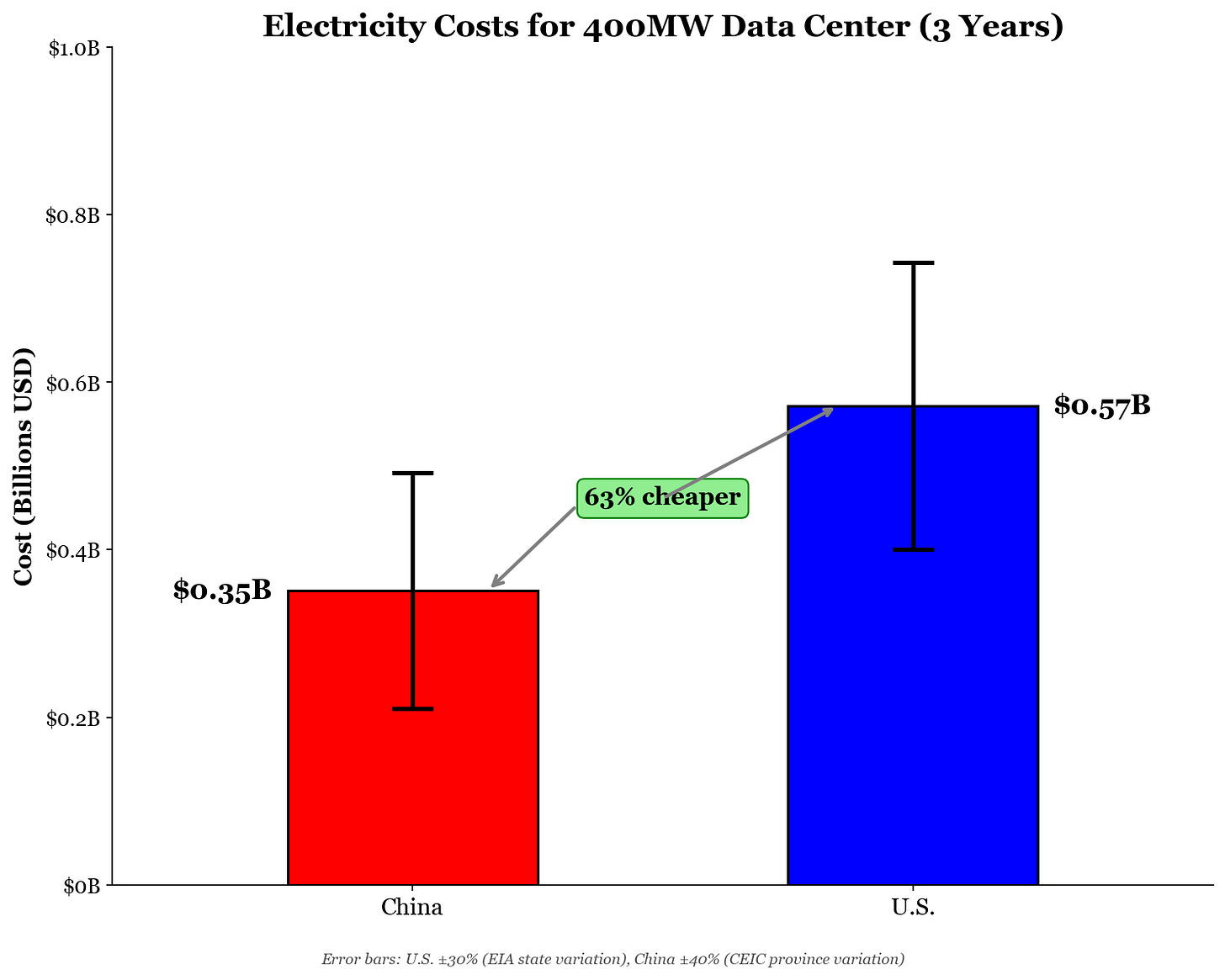

Nearly all of the cost differential comes from two factors: construction and hardware. Other costs, including commonly covered topics like electricity and water, are essentially rounding errors. As such, the main article only covers those two bills, but calculations for everything else are included in the appendix. Because these calculations require some assumptions, I vibe-coded a website that allows you to play with my assumptions and see how the numbers change.

We Run the Numbers

For simplicity’s sake, I will estimate the cost of constructing and operating a 400MW data center over three years. Microsoft’s 400MW Fairwater 1 in Wisconsin is currently the largest AI data center by MW and has decent public information about it, so I’ll take that as our benchmark. I will also limit the operating timeline to three years because data center GPUs often have lifespans for only that long.1 I’ll run through the calculations below, with exact numbers and calculations in footnotes.

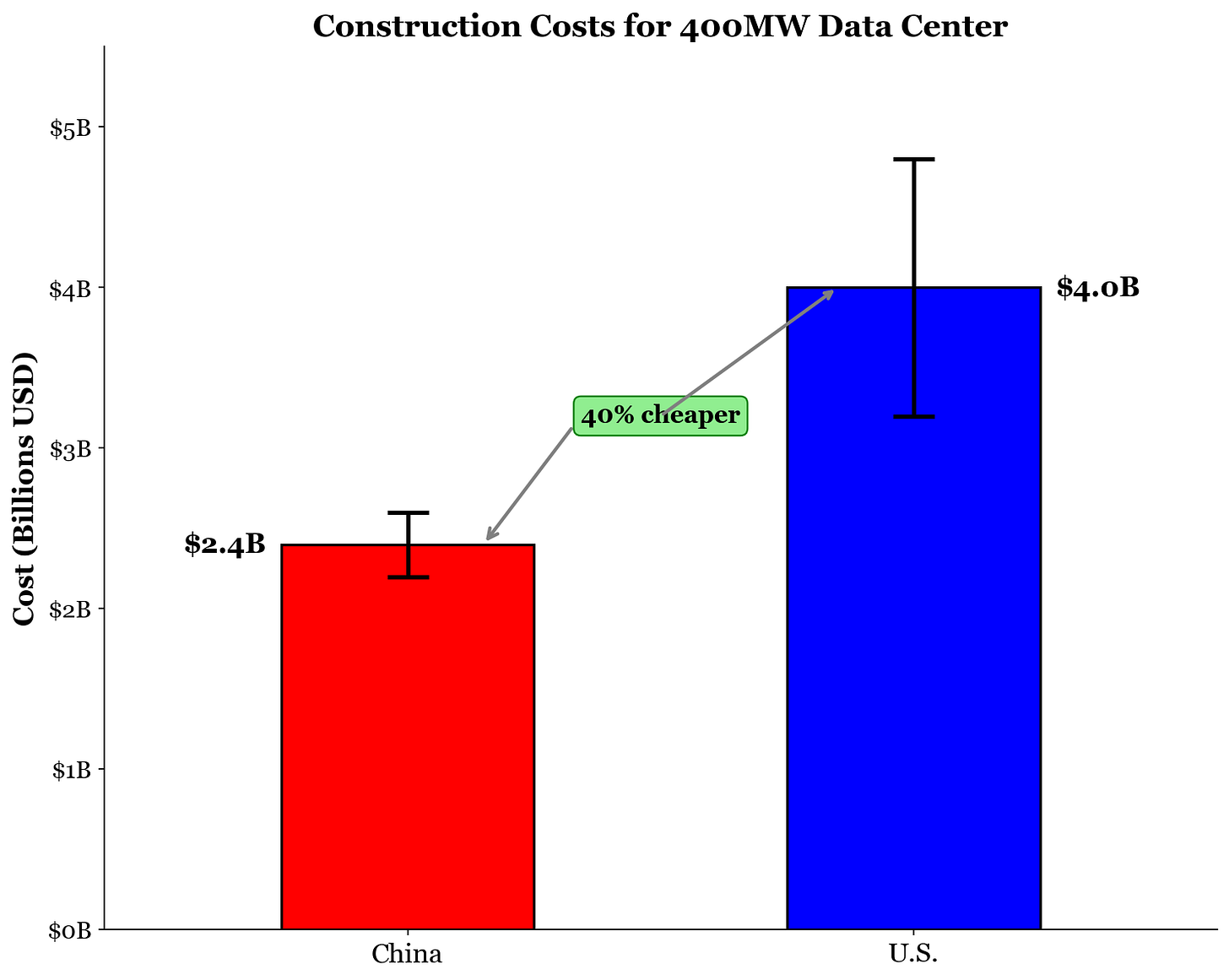

Construction

Constructing a data center takes an enormous amount of capital. The plots can be enormous, as demonstrated by China Telecom’s Inner Mongolia Information Park spanning over 10 million square feet. Here, China has the edge. With cheaper labor and quicker construction times, Chinese data centers take the low end on construction costs.

In China, data centers usually cost $5.5 to $6.5 million per MW for construction, so I will assume that the average Chinese data center would run closer to $6 million per MW. In the U.S., on the other hand, data centers cost about $8 to $12 million per MW, so I will assume a cost of $10 million. These costs depend significantly on the site location, redundancy requirements, and other factors, so averages are the best we can achieve here.

For a 400MW data center, then, construction in China would be about $2.4 billion, while in the U.S. it would be about $4 billion. That means construction alone would save China $1.6 billion.

Hardware

The other one-time fixed cost for our data center is the hardware. This is the U.S.’s biggest advantage. Because of export controls, the hardware stocked in Chinese data centers would not be as efficient as their American counterparts. The current best Chinese product for AI servers is Huawei’s CloudMatrix384 (CM384), which costs about $8 million dollars to purchase and is able to perform nearly double the floating-point operations per second (FLOPS) compared to Nvidia’s GB200 NVL72; however, the CM384 consumes much more power, eating up nearly 600,000 W per unit. By contrast, Nvidia’s product costs about $2.6 million and only consumes a quarter of the power.2 This means that a Chinese data center would not be able to accommodate nearly as many CM384s as an American data center would be able to host GB200 NVL72s.

Besides power consumption reasons, a Chinese datacenter might be crunched to accommodate many CM384s due to China’s silicon constraints. As of writing, no CloudMatrix384 has been produced with fully indigenous Chinese components. Although Chinese SMIC is beginning to lessen the dependence on TSMC for dies, the lack of domestic HBM is a pressing issue for Huawei. They must rely on a dwindling pile of stockpiled HBM from foreign memory makers, so their total capacity for production is severely bottlenecked. So please, take the theoretical maximums with a mountain of salt.

For a 400MW data center, roughly 90% of the power will actually go to serving hardware, with the rest reserved for cooling, networking, lights, and all other power needs.3 Of that hardware power, SemiAnalysis estimates that 48 MW goes to standard CPUs and storage, while the rest goes to GPUs, leaving about 312 MW for the real workhorses.4

With 312 MW reserved for powering hardware, an American data center could accommodate a maximum of 2,154 GB200 NVL72s, while a Chinese data center could accommodate only 520 CM384s.5

With more racks being purchased, though, American data centers would spend more on hardware costs. For nearly 2,200 Nvidia racks, an American data center would spend just over $5.6 billion on hardware while a Chinese one would spend nearly $4.2 billion.6 A Chinese data center would be spending about 25% less on hardware for the price of purchasing many fewer units.

However, the Trump administration’s decision to permit the sale of H200s to China offers a stronger option for China and potentially alleviates their silicon constraints.

A popular server solution with the H200 is the DGX H200, priced at about $450,000, but the exact cost for Chinese consumers is still unknown; bulk discounts, the Trump admin’s 25% cut, and no official pricing means no one truly knows.7 Although the DGX H200 has a maximum power usage of 10,200 W, we must also account for external networking; unlike the GB200, NVL72, and CM384 — which are rack-level solutions — the H200 only offers node-level solutions, and we must calculate the overhead for network communication between nodes.8 Factoring that in, the theoretical maximum number of DGX H200s in a 400MW data center is then just under 30,000.9 It is important to note that hyperscalers likely do not use the DGX H200, but rather rig up the base H200s in their own way; however, this calculation uses the DGX H200 as a reference point.

For a more apples-to-apples comparison, I will refer to nine DGX H200 nodes networked together as a single “DGX H200 pod,” as this theoretical pod would have as many Nvidia GPUs as a GB200 NVL72. In this case, a 400 MW data center could accommodate a theoretical maximum of just under 3,300 DGX H200 pods.10 The cost of that many DGX H200 pods would run a Chinese data center over $13.8 billion dollars.11

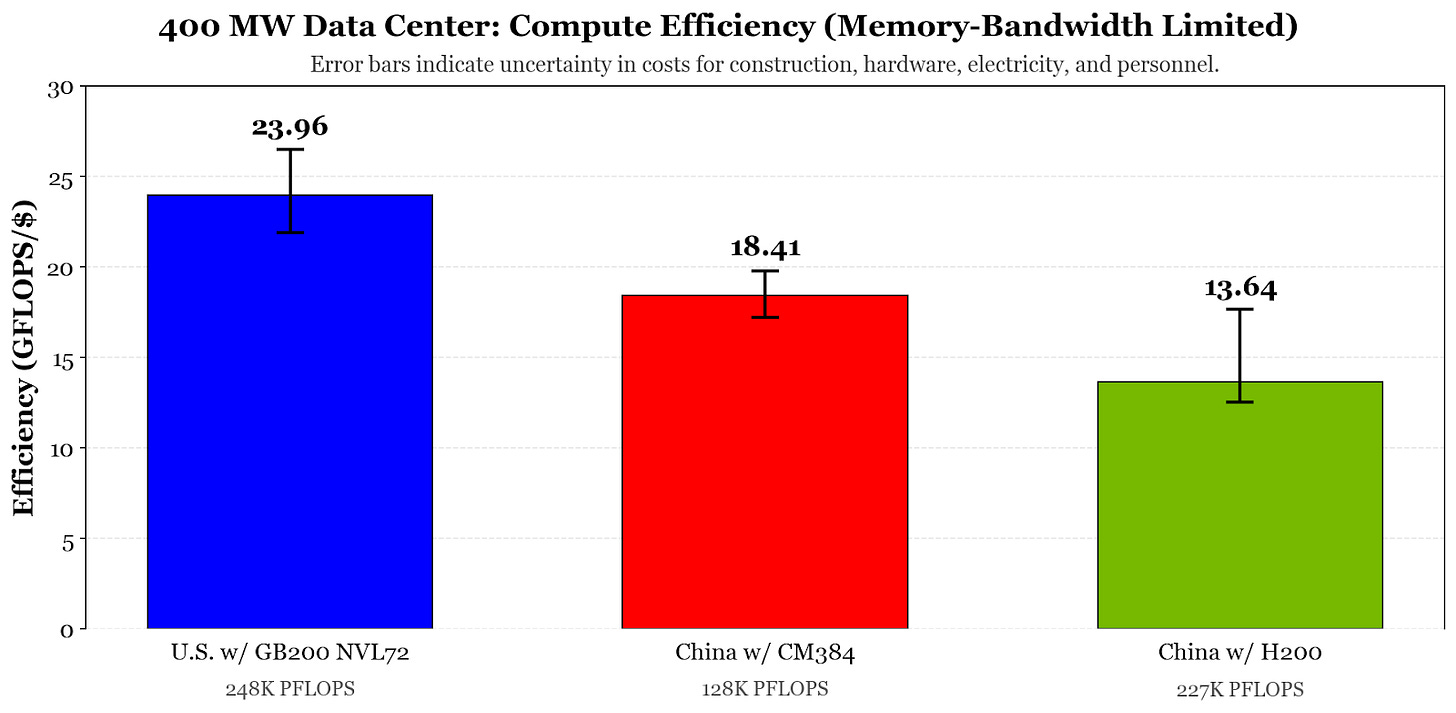

Although access to the H200 gains significantly more “AI” for China compared to the CloudMatrix384, the total computing power and efficiency of compute would still be less compared to an American data center. For training workloads, the American data center would be able to perform nearly 250,000 PFLOPS, whereas a Chinese data center with the H200 or CloudMatrix384 would only be able to achieve over 226,000 PFLOPS or nearly 130,000 PFLOPS, respectively.12 The exact process for calculations is discussed in the appendix, but it is worth noting that only the GB200 NVL72 can support FP4 precision, which would nearly double its performance for inference workloads.

The hardware calculations show the H200 puts China within close reach of the U.S. More importantly, though, the H200 gives China hardware to stock its data centers that it would otherwise not have with supply-limited CloudMatrixes.

Final Comparison

Adding it all together, China can make data centers significantly cheaper than the U.S. can.13 By saving on construction, China would have the advantage in raw cost for a data center buildout.

But that doesn’t mean that China has the advantage. Considering the relatively small number of racks of CM384s a Chinese data center would be able to accommodate, the AI workloads a Chinese data center would be able to perform would be much smaller as a result. The sheer number of GB200 NVL72s in an American data center means that the U.S. could accommodate almost double the PFLOPS of GB200 racks compared to CM384s. Those efficiency gains by the U.S. more than compensate for the cost gains made by China.

However, with the H200, China would be able to shrink that gap considerably. The cost savings in construction and other bills permit China to reach a similar FLOPS per dollar compared to an American data center.

Conclusion

China can build cheaper, but the U.S. can build better. However, the simple calculation elides away key constraints binding both American and Chinese efforts for data center dominance.

For China, the silicon constraints are real. Although they can manufacture CM384s, which are subpar compared to equivalent Nvidia products already, they cannot manufacture many of them. The relatively slow pace of Chinese chip manufacturing due to export controls and bad yield poses a serious issue for data center ambitions.

Today, many data centers in China are sitting idle due to the combination of a lack of cutting-edge chips and the yet-to-arrive massive AI demand. It will not matter how cheaply China can build a data center if they don’t have chips to stock them or models to constantly use them. Tencent cut its capex by 25% last year because of a lack of access to chips, whereas American hyperscalers are expected to increase capex by over 35% for 2026.

The recent H200 ban lift may reverse this trend, allowing China to stock data centers with chips they might not otherwise have. However, Nvidia’s limited supply of H200s and the potentially strict rules on export licenses may mean that even the H200 news will not solve China’s problems. Besides the H200, though, China may be able to address its domestic compute limitations with remote cloud access to compute abroad.

For the U.S., electricity constraints are worrying. The U.S. has a small power supply compared to China, and expansion is likely required to accommodate the rate of data center buildouts. Either that, or start building abroad in energy-rich nations. Without addressing these energy problems, the cost of electricity for data centers and Americans alike will likely rise, increasing the already high costs for American data centers. At some point, there might not be enough energy in certain locations to justify more data centers. Combined with slow permitting procedures, this is a tricky problem to solve.

Whether it’s chips for China or electricity for the U.S., whichever nation can solve its constraints will likely have the final laugh in the data center fight.

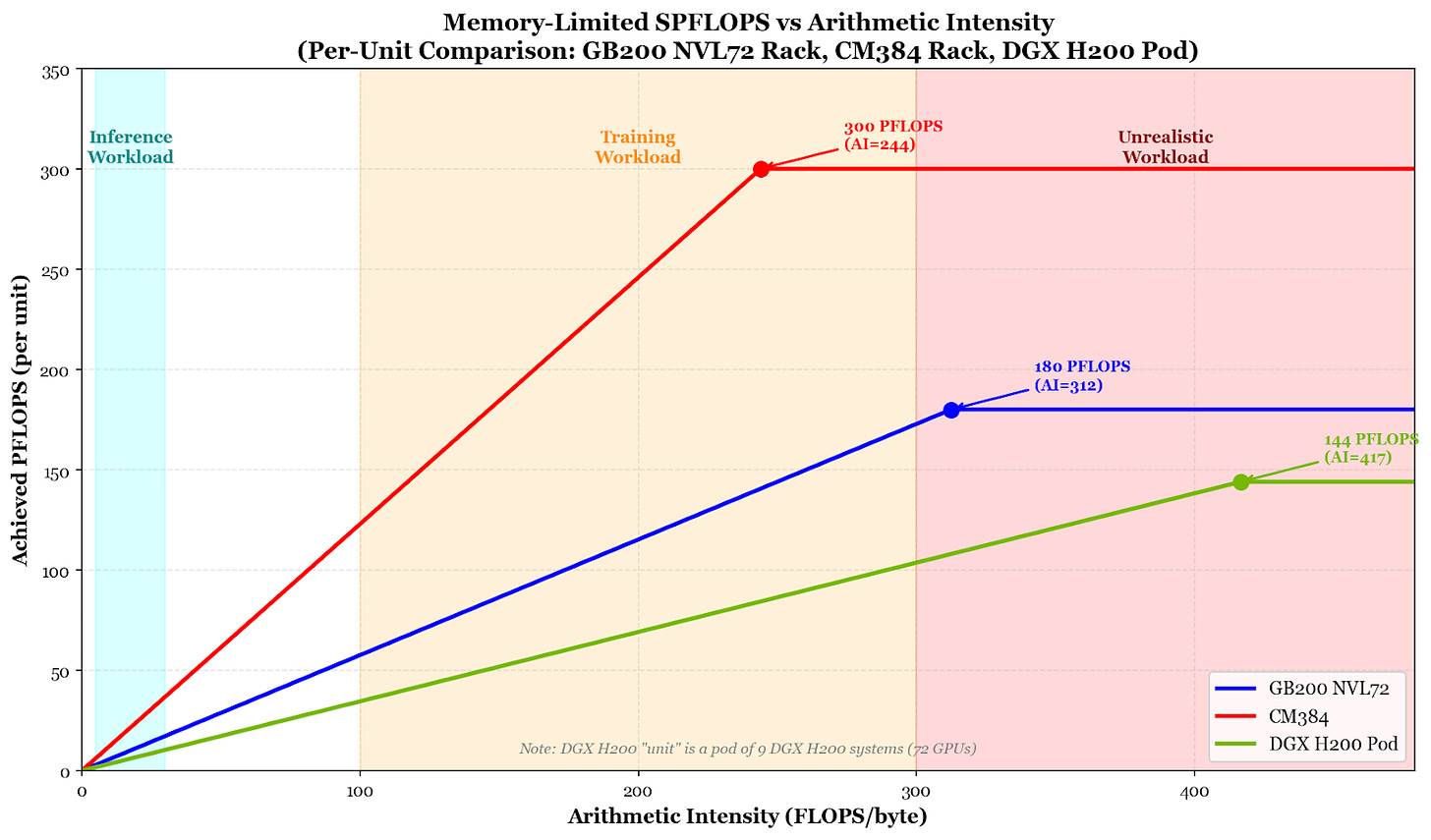

FLOPS Calculations

The performance of hardware was not measured based on the peak FLOPS that they are marketed to have, as chips nearly never achieve that level of computational intensity. Instead, hardware is typically “memory bound,” meaning some compute is sitting idle waiting for memory to fetch it data on which to perform operations. The way to calculate the amount of usable FLOPS a system has is by understanding the hardware’s memory bandwidth and the number of FLOPs required for each byte of data transferred by memory, or the arithmetic intensity. This number depends on the size of the model and whether we are performing inference or training, but a healthy number for large training workloads is an arithmetic intensity of 200 FLOPs per byte14. The vibe-coded site allows you to modulate the arithmetic intensity to see the range in cost effectiveness.

Although the number of H200s a Chinese data center would be able to accommodate lends an even greater number of peak FLOPS compared to the GB200 NVL72, the memory bandwidth of the DGX H200 is extremely constraining. The HBM bandwidth of the GB200 NVL72 and CloudMatrix384 is 576TB/s and 1,229 TB/s, respectively, whereas the DGX H200 pod would only have about 345.6TB/s.15 Thus, at an arithmetic intensity of 200 FLOPs per byte, no piece of hardware would reach its theoretical max performance, but instead cap out at the aforementioned SPFLOPS. An unrealistic sustained arithmetic intensity of 417 FLOPs per byte is required for the DGX H200 to reach its theoretical maximum, meaning that the GB200 NVL72 will reliably outperform it due to superior memory bandwidth.16

The calculations did not account for the effects of network overhead. The effect of network bandwidth on achievable FLOPS is still debated, as workloads can be optimized to minimize the need for network communications. Although network bandwidth almost definitely limits the achievable FLOPS for different workloads, calculating the extent of its limitations is highly variable.

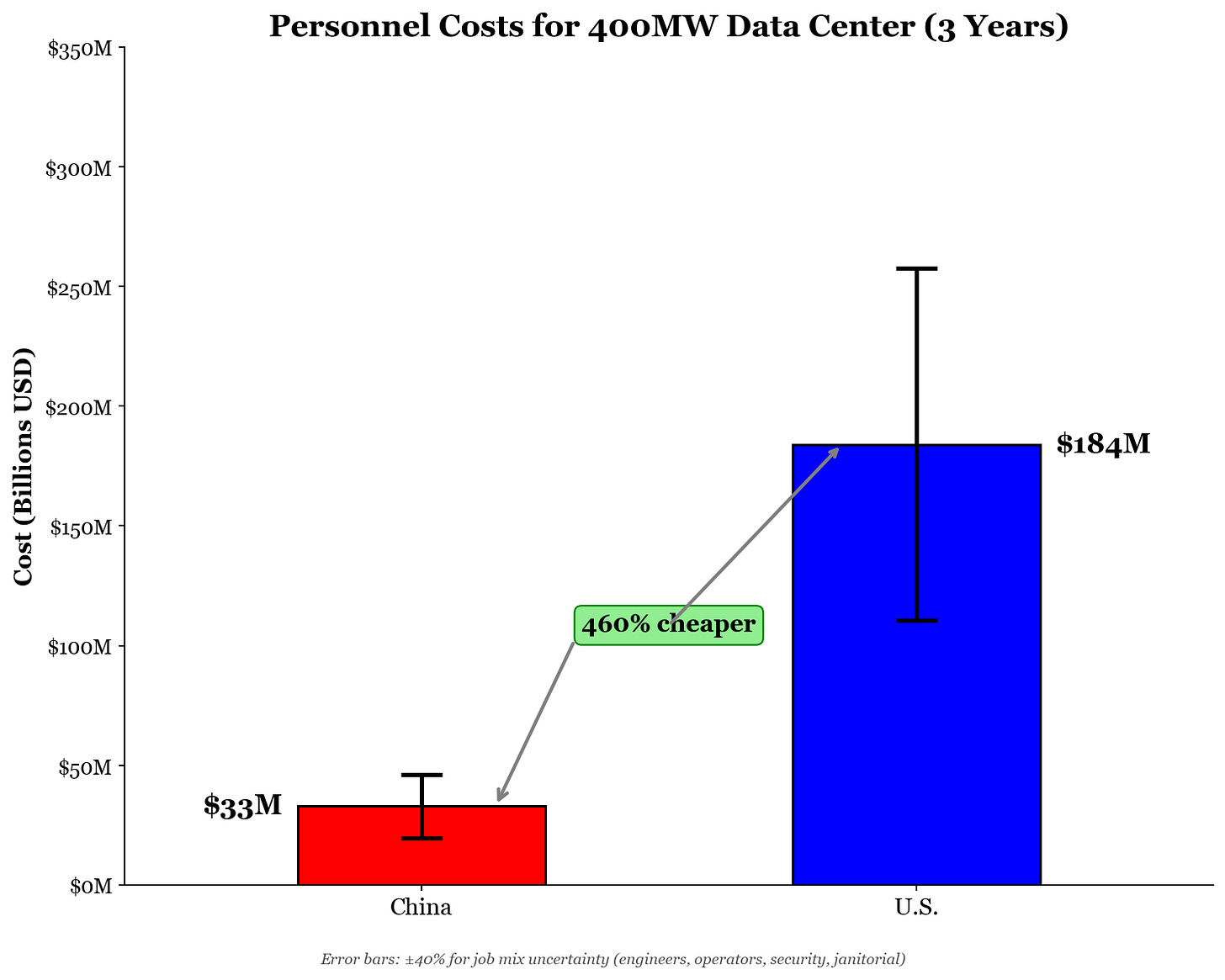

Electricity, Water, People, and ‘Emotional Turmoil’

Below are the calculations and explanations for costs not included in the main article, namely electricity, water, and personnel. Although these costs seem significant due to their press coverage and size when taken in isolation, compared to the main costs of construction and hardware, these are essentially insignificant.

Electricity

For powering a data center for three years, China’s massive electricity buildouts give it the edge. A kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity for industrial users, on average, costs about 9 cents in the U.S. while only 6 cents in China. In reality, these electricity costs are likely lower for both nations, as data centers tend to make deals to secure lower energy prices for large-scale projects. However, I will assume that the prices are relatively analogous.17

Fortunately for their wallets, data center constructors don’t actually pay for 400 MW of electricity. Although that is the maximum amount of power they can accommodate, GPUs aren’t running 100% of the time. On average, they are utilized 80% of the time for training purposes, while closer to 40% for inference. I will just cut it down the middle and assume a 60% utilization rate, which other data confirms. Thus, only needing to power about 240MW at any given moment, for 8,760 hours a year, for three years, a Chinese data center would spend about $350 million on electricity while an American one would spend just under $600 million. That’s nearly 40% in savings for a Chinese data center.

Personnel

A data center also needs people to operate it. Fairwater 1 will employ about 500 full-time employees, and salaries for all that personnel are not a negligible cost.18 For an average data center, labor costs run about 15% of annual expenses and nearly 5% of total cost; however, for advanced data centers requiring more expensive, leading-edge equipment, labor costs will take up a smaller slice of the pie.

Again, labor is cheaper in China, so the cost factor is in China’s favor. The average salary for a data center operator in the U.S. is above $120,000 a year, while a similar job in China only pays about $22,000 annually. Although not every job in a data center is a data center operator, I’ll use these salaries to extrapolate costs for payroll for all 500 employees. Because of this extrapolation, this calculation is likely overestimated and has the largest margin of error.19 However, given the relative unimportance of personnel costs compared to the main bills of construction and hardware, it doesn’t make much of a difference.

Because of the great pay differences, though, an American data center would spend over $184 million on personnel for three years, while a Chinese one would spend almost $33 million. Here, a Chinese data center saves more than 80% compared to an American data center!

Water

For all the articles about water and datacenters, its relevance to operating costs is quickly disappearing. Running all those GPUs creates a great deal of heat, so data centers must utilize cooling systems to ensure the hardware doesn’t overheat and malfunction. Cooling systems use enormous amounts of water, and, once again, water is cheaper in China. In the U.S., water costs about $5.18 per thousand gallons, while it costs nearly half that ($2.57) in China.

Microsoft’s Fairwater 1 will consume 2.8 million gallons of water per year, so I’ll use that number for our estimate; in reality, this number can fluctuate depending on data center layout and the type of cooling system used. Newer data centers are using more efficient cooling methods like Fairwater 1’s closed-loop cooling, including free cooling, air cooling, and immersion cooling. Thus, Fairwater 1’s water usage number will likely be closer to future data center buildouts compared to the significantly more water-hungry data centers in previous years.

For that much water for three years, the U.S. would spend more than $40,000 for water, while China would spend just above $20,000. This more than 50% decrease in water spending for China may seem important, but with other costs being on the magnitude of millions and billions, the thousands spent on water seem negligible.

Emotional Turmoil

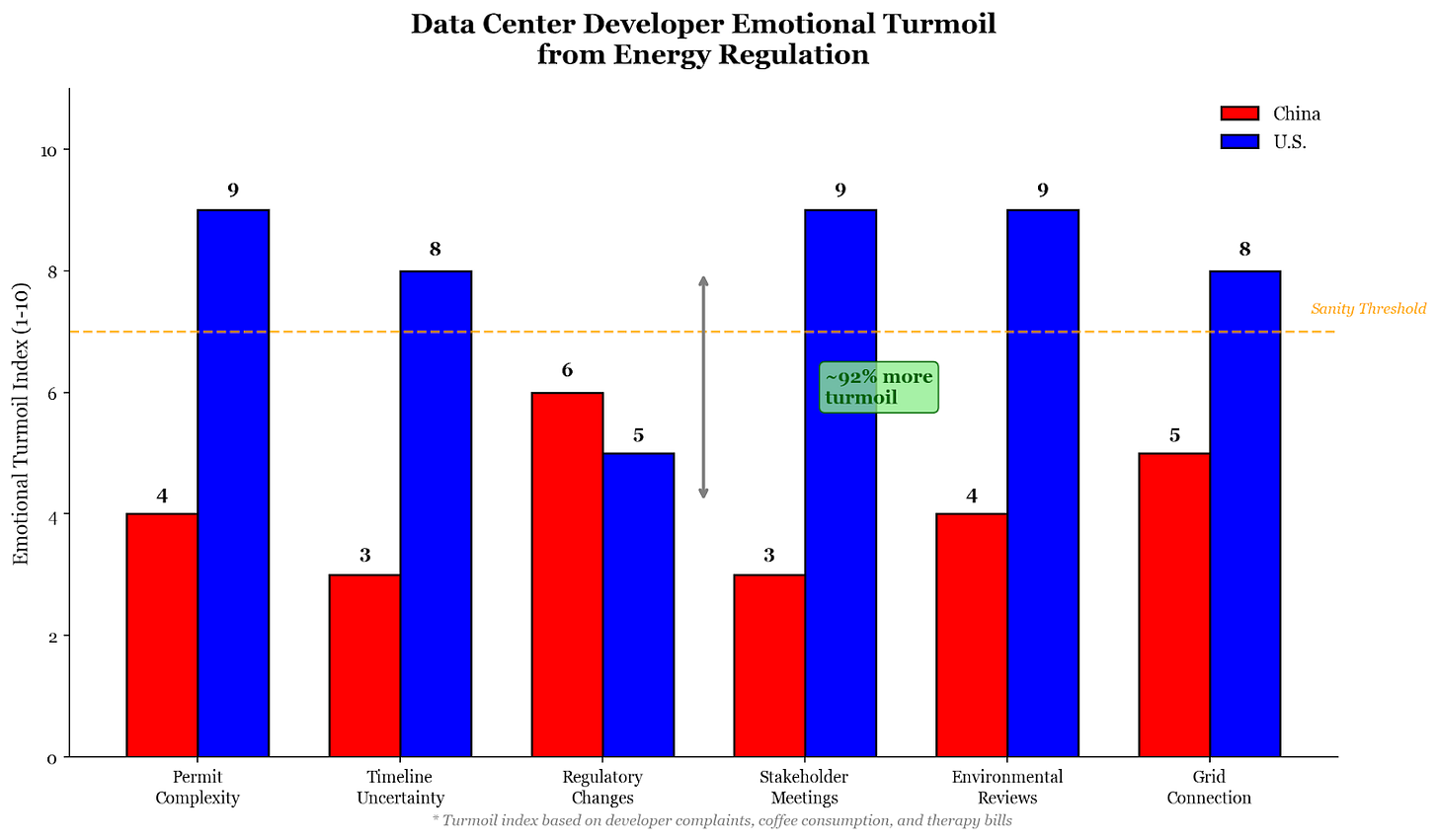

Besides financial burdens, data center developers also face other kinds of costs. A former White House staffer who worked on chips permitting said that this BOTEC needed a chart quantifying “developers’ emotional turmoil from engaging with U.S. energy regulation.” The gauntlet of energy regulations, permit processes, and construction timelines constitutes a serious challenge for the mental health of hyperscalers. After a deep analysis, Claude Code suggests that American developers face ~92% more emotional turmoil due to these regulations, consistently breaking the expected “sanity threshold” for such projects.

Regardless of the objective quantitative analysis of costs, China’s advantage in emotional health for developers may give it an edge in the AI race. However, the persistent trend of American developers building out exponentially more than their Chinese counterparts may represent American resilience to such challenges. Or perhaps such a trend represents the masochism needed to sacrifice at the altar of progress and superintelligence.

Some conversations indicate that the lifespan can actually be much longer, and three years is simply when it is more cost-effective to upgrade the hardware.

Reporting indicates a ~10% margin of error for the pricing of these units.

90% corresponds with a power usage effectiveness (PUE) of about 1.11. Hyperscalers like AWS, Google, Microsoft, and Meta report an average PUE of 1.15, 1.1, 1.18, and 1.08, respectively. Larger, newer facilities tend to have a better PUE due to the emergence of more efficient cooling systems and data center design.

(400MW/1.11) - 48MW ≈ 312MW.

For GB200 NVL72 – ⌊((400MW/1.11 PUE) - 48MW) × 1,000,000 W/MW)/145,000W per rack⌋ = 2,154 racks; for CloudMatrix384 – ⌊((400MW/1.11 PUE) - 48MW) × 1,000,000 W/MW)/599,821W per rack⌋ = 520 racks. These are definitely the upper bounds of hardware purchases, as space, power constraints, and scale-out resource drain would mean much fewer being utilized, but these numbers will work for a BOTEC. This BOTEC also elides the networking costs beyond the rack level, as they will likely be similar for each piece of hardware, and the costs greatly depend on the data center’s configuration.

For GB200 NVL72 – $2,600,000 per rack × 2,154 racks = $5,600,400,000; for CloudMatrix384 – $8,000,000 per rack × 520 racks = $4,160,000,000.

This article assumes the cost of $450,000, the middle of the range listed by the hyperlinked source. However, the range (with moderate confidence) of the cost is between $322,500 to $500,000, as this accounts for the high end of the source and the conservative estimate of 1.5 times the 8-GPU baseboard cost of $215,000.

Each DGX H200 node requires approximately 0.38 InfiniBand switches, and given each switch consumes about 1000 W, networking adds about an extra 380 W in power usage for each node. The ratio of total switches (the sum of leaf switches and spine switches) to nodes for each configuration of SU is approximately 0.38. The QM9700 switches consume 747 W with passive cables and 1,720 W with active cables, so we use a rough average of 1,000 W given the mix of active and passive cables for large-scale deployment.

(((400MW/1.11 PUE) - 48MW) × 1,000,000 W/MW)/(10,200W + 380 W) per node = 29, 523 DGX H200 nodes.

⌊29,523 DGX H200 nodes × (1 pod per 9 nodes)⌋ = 3,280 DGX H200 pods.

$450,000 per DGX H200 × 3,280 pods × 9 DGX H200s per pod = $13,284,000,000. 8 cables per node × 9 nodes per pod × 3,280 pods × $420 per cable = $99,187,200 for cables. The price for cables was estimated based on a rough average of the cost of active and passive cables, but the cost could range drastically depending on the connector, protocol, and length. 0.38 switches per node × 9 nodes per pod × 3,280 pods × $40,000 per switch = $448,704,000 for switches. The price for switches was estimated based on a rough average of the range of prices found online. $99,187,200 for cables + $448,704,000 for switches = $547,891,200 for switches and cables. $547,891,200 for cables and switches + $13,284,000,000 for pods = $13,831,891,200 total.

For BF16, commonly used for training, and assumes arithmetic intensity of 200; for GB200 NVL72 — 576 TB/s per rack × 2,154 racks × 200 FLOPs per byte × 1P/1000T = 248,140.80 PFLOPS; for CloudMatrix384 — 1,229 TB/s per rack × 520 racks × 200 FLOPs per byte × 1P/1000T = 127,816 PFLOPS; for DGX H200 pods — 345.6 TB/s per pod × 3,280 pods × 200 FLOPs per byte × 1P/1000T = 226,713 PFLOPS.

Other costs like property taxes could also be factored into a true operating cost for a data center, but such specific calculations do not a BOTEC make. Property taxes and other fees are constantly abated and negotiated for each data center, so no estimated cost would be useful here regardless.

200 FLOPs per byte was reached by a rough average of arithmetic intensity from the mix of high-intensity GEMMs and non-GEMM operations during training.

The H200 GPU has a bandwidth of 4.8TB/s. 4.8 TB/s per H200 × 8 H200s per DGX H200 × 9 DGX H200 per pod = 345.60 TB/s per pod.

Measuring the theoretical maximum for BF16, most commonly used for training.

This calculation includes the margin of error for statewide variation in the U.S. and provincial variation in China.

Full-time staff at data centers include site leads, technicians, engineers, security personnel, and janitorial staff. The number of staff is less dependent on electricity workloads and more dependent on the square footage of the facility and the maintenance needs of systems. 500 full-time employees is definitely on the upper end of the spectrum, with other facilities only needing dozens to a hundred full-time employees.

Research into salaries for security personnel, janitors, and other staff leads to about a 50% margin for error.

Like this comment if you think ChinaTalk needs a data visualization assistant (human or AI).

Jensen always talks about $40-60b 1GW datacenter cost.

Extrapolating your numbers, we get $26b for 1GW. Dont you think you are underestimating?

Thanks, big fan here!