Longing for the Cultural Revolution in China Today

why some youth crave the 60s: internet leftism and misplaced yearning

Today’s guest contributor brings a fascinating analysis of young online leftists in China, focussing on their ideology, social and political context, and how a Feng Xiaogang film inspired them to romanticize the Cultural Revolution.

Shijie Wang is an open-source researcher and Deputy Editor at The Jamestown Foundation’s China Brief. He completed a Master’s in Public Policy at Georgetown University. His research focuses on China’s domestic issues, foreign operations, and critical minerals; he also analyzes China’s strategic moves in the minerals sector through his personal Substack.

The “Fanghua” Incident

In November 2025, a content creator named “Liao Hui Dian Ying Ba” (Let’s Chat Movies, 聊会电影吧) on Bilibili, China’s largest video-sharing platform, uploaded the first installment of his analysis of Feng Xiaogang’s (冯小刚) film Fanghua (Youth, 芳华). Released in 2017, Fanghua follows the lives of several young members of a military performance troupe in southwestern China from the 1970s to the 1990s. The film places them against a backdrop of turbulent historical transitions: from the tail end of the Cultural Revolution and the Sino-Vietnamese War to the rise of Shenzhen during the Reform and Opening-up era, depicting the divergent fates of its characters. At the time of its release, the film was a box-office success, launched the careers of several young actors, and earned a respectable 7.7/10 rating on Douban Movie, China’s IMDB. However, once it left theaters, the film largely faded from public discourse — until this creator’s analysis surfaced.

Subsequently, the creator uploaded a second analysis video. In his commentary, he frequently referenced other critically acclaimed Chinese cultural products, such as Ming Dynasty 1566 (大明王朝1566), Let the Bullets Fly (让子弹飞), and In the Heat of the Sun (阳光灿烂的日子). By cryptically hinting at the film’s hidden political metaphors, he quickly attracted a massive audience of young viewers. They showered the video with likes, reposts, and “coins” (投币) — a Bilibili feature that allows users to tip or donate to content creators as a sign of endorsement.

The climax of this saga occurred on November 29, when “Liao Hui Dian Ying Ba” uploaded his third analysis of Fanghua. Perhaps frustrated by persistent questions in his private messages, he began the video by declaring that he would no longer hide behind euphemisms; instead, he would explicitly reveal the film’s “true” political agenda. In doing so, he completely overturned the official verdict on the Cultural Revolution found in Chinese history textbooks. He claimed that Fanghua was, in fact, telling the suppressed true history of a “great people’s revolution” now concealed by today’s entrenched elites.

He argued that the protagonist, Liu Feng (刘峰) — a moral paragon within the military who is eventually abandoned by his superiors and marginalized by the elite during the Reform era — is a proletarian hero. To this creator, Liu Feng symbolizes Wang Hongwen (王洪文), the factory worker who rose to the Politburo Standing Committee and became a member of the hugely influential Gang of Four, only to be purged by elites after the “failure” of the Cultural Revolution. Conversely, the other characters represent the business elites and “red aristocracy” associated with the Deng Xiaoping faction — the very targets Mao Zedong sought to eliminate during the Revolution. The film’s ending, which finds Liu Feng in abject poverty while his former peers become real estate tycoons or emigrate to the West, was interpreted as a symbol of the revolution’s betrayal. It was the fulfillment of Mao’s greatest fear: the comeback of the capitalist elites. At the end of the video, the creator affectionately referred to Mao as “Big Brother” (老大哥), asserting that Mao’s vision was simply “too far ahead of its time” for people to grasp, leading to the regretful state of contemporary China.

Within five days of its release, the Fanghua series amassed 37 million views, with over 10,000 concurrent viewers at any given moment. Among the millions of interactions, the comments section was flooded with slogans such as “Long live the people!” and “Carry [the Cultural Revolution] through to the end!” However, on the fifth day, Bilibili removed all three videos and deleted the creator’s account. Rumors circulated that he had been summoned by local police, though no definitive evidence emerged to confirm this. It was reposted on YouTube though! (if this link goes down in the future just search on youtube the following and another mirror will pop up: 聊会电影吧 芳华 无删减 三部合集)

Despite the disappearance of the videos and the account, this revisionist ideology persisted. Bilibili users continued to post radical comments under related videos, and the analysis was re-uploaded to “safer” platforms or circulated privately. Given that the majority of Bilibili users are young people under 25 — mostly students — they have no lived experience of the decade-long Cultural Revolution. Why, then, are so many of them collectively yearning for a return to a period officially designated as a ten-year catastrophe? The answer lies in the origins of this ideological trend.

The Rise of the “Net Left”

This ideological shift stems from an emerging group known as the “Net Left” (wang zuo, 网左), which is predominantly composed of — and popular among — students. The “Net Left” possesses neither a unified manifesto nor a cohesive organization; rather, it is a wave of public opinion that coalesced through a series of events. Because this group adheres to radical left-wing populist views but operates almost exclusively in digital spaces, never convening in person or organizing offline activities, the public dubbed them the “Net Left.” This moniker serves to distinguish them from the older, more academically established “New Left” (xin zuopai, 新左派) that was previously prominent in Chinese intellectual discourse.

The “Net Left” traces its earliest roots to a niche group on Weibo between 2011 and 2015 known as the “Franco Left” (fa zuo, 法左). This term referred to a small circle of leftists who adhered to French postmodernist philosophy. The group was highly exclusive with a significant intellectual barrier to entry, consisting primarily of Chinese students studying humanities and arts in Europe and the United States.

Their theoretical mentor at the time was Lu Xinghua (陆兴华), then an associate professor of philosophy at Tongji University in Shanghai. In late 2013, Lu began translating and disseminating the theories of French philosopher Alain Badiou on Weibo. Crucially, this included Badiou’s laudatory perspective on the establishment of the Shanghai People’s Commune (上海人民公社) during the Cultural Revolution (as detailed in Badiou’s works Petrograd, Shanghai: les deux révolutions du XXe siècle and L’Hypothèse Communiste). Ultimately, however, the dense jargon of postmodern philosophy proved too obscure for the public, limiting the group’s reach. As the Chinese digital landscape shifted into an era dominated by the pro-establishment “Little Pinks” (xiao fenhong, 小粉红), this critical and radical left-wing current largely receded from public view for several years.

The tide turned in 2019, when the “996.ICU” movement, a protest launched by tech workers against relentless overtime schedules, re-energized radical left-wing voices in the public sphere. During this period, the language of Cultural Revolution nostalgia resurfaced in the Chinese digital world. Alibaba founder Jack Ma, once affectionately nicknamed “Daddy Ma” (马爸爸), was suddenly rebranded as a “capitalist” who deserved to be “strung up from lamp posts” (挂路灯), a nod to the French Revolutionary cry “À la lanterne!” This sentiment was further fueled by a series of financial scandals involving entertainment celebrities. Most notably, the alleged insider trading scandal of idol actress Vicki Zhao (赵薇) pushed more people into the ranks of the anti-capitalist radical left.

During this era, the burgeoning movement abandoned the dense jargon of European postmodernism. Instead, it distilled its discourse into a binary struggle: the “compradors” (买办) and “capital” (资本) versus the “exploitation” (剥削) of “the people”. This simplified narrative attracted a massive influx of young people who were frustrated with their poverty and pressure but struggled to find an answer. Suddenly, the solution was no longer buried in thousands of pages of Deleuzian tomes. Everything was reduced to a single, omnipotent, and evil symbol: “capital.” This shift represented the instrumentalization of theory as a weapon. Realizing that complex European philosophy could not directly address the injustices of their reality, these young people stripped away the philosophical nuance, leaving behind only the most radical forms of struggle.

The final catalyst that solidified the self-identification of these radical left followers was the massive public debate surrounding the term “small-town test-takers” (xiaozhen zuotijia, 小镇做题家) in May 2020. This group consisted of elite university graduates coming from China’s third- and fourth-tier cities or rural areas who found themselves utterly unable to compete with their peers from developed regions in the job market. They mocked themselves as people from small towns who were good at nothing but taking tests, lacking the necessary social capital to succeed. Consequently, they felt they had rapidly degenerated into “losers” upon leaving the ivory tower (given the fact that youth unemployment rate in China is 16.9%). As the online discussion ignited, the scope of this concept expanded; many current students still inside the examination hamster wheel began to identify with this label, gradually transforming their self-mockery into collective anger.

This event was pivotal for the formation of a broader radical left contingent. The rhetorical resonance of the “small-town test-taker” represented the bankruptcy of an implicit social contract that had sustained the Reform era since the restoration of the National College Entrance Examination in 1977, immediately after the end of the Cultural Revolution. This contract promised that through hard work and high scores, one could secure a prestigious career and achieve upward social mobility. Naturally, young people began to question why schools, families, and society continued to propagate the illusion that this contract still held, even as they endured ten-plus hours of repetitive testing a day in the schools.1

During this period, the revived Maoist rhetoric of the radical left provided a seductive and simple answer: it was “capital” that forced them into this grueling competition; it was “capital” that led to the inequitable distribution of resources.2 The discourse of the “Net Left” offered no sophisticated explanation as to why capital would necessarily produce this outcome, nor did it need to. Its primary function was to provide the disillusioned with an externalized explanation that absolved individual responsibility for their perceived failure.

Thus, a cohort of youth harboring a profound animosity toward “capital” emerged. Comprising both students and recent graduates, these individuals typically hail from China’s underdeveloped hinterlands or impoverished urban families in developed coastal cities. They fostered a mutual identity rooted in shared precarity, converging on the conviction that their only salvation lay in a “people’s revolution” to topple “capital.”

The “Net Left” had officially taken shape. They claimed cyberspace as their primary battlefield, venting frustrations against the status quo and aggressively assaulting anyone who rejected their binary framework of “the people vs. capital.” Because this community was forged through a combative identity rooted in rage, they projected a disproportionately loud volume online, creating an illusion of a massive, mainstream movement representing the majority’s will.

However, it is crucial to distinguish the “Online Left” from the “Little Pinks”, despite both appearing patriotic at times. The Net Left does not blindly subscribe to all official nationalist narratives; they weaponize nationalist tropes only when condemning the United States, which they see as the beacon of capitalism. More often, they maintain a radical leftist anti-establishment stance, fiercely criticizing current wealth distribution policies. Consequently, unlike the Little Pinks — who often enjoy official endorsement — the Net Left is treated by the state’s censorship apparatus with the same heightened suspicion as other dissident groups.

The Psychological Cause: Cult of the Vanquished

As previously discussed, a cornerstone of the “Net Left” identity is the “small-town test-taker,” the definitive losers in China’s relentless rat race. As casualties of this competition, they are the ones most acutely facing high unemployment, rigid class stratification, and even “sexual frustration” (性萧条), a term introduced by then chief editor of Global Times Hu Xijin (胡锡进), referring to young people in China who are now struggling to have romantic relationships. However, unlike the neoliberal work ethic prevalent in China from the 1990s to the early 2000s, which demanded that the unsuccessful reflect on their own lack of effort, “Net Left” theory provides a logic of moral purity. It posits that in a world monopolized and corrupted by “capital,” secular success is an inherent betrayal of one’s soul. Consequently, being a “loser” is no longer a mark of incompetence; it becomes a badge of honor, symbolizing a refusal to compromise with a wicked order. This sense of moral superiority transforms their social death into a form of tragic, heroic resistance. The Social Darwinism that once dominated Chinese social thought is thus completely inverted by the “Net Left”: “survival of the fittest” (胜者为王) is spat upon, while poverty and failure are re-sanctified — a dynamic reminiscent of the “class origin” theory (出身论) during the Cultural Revolution, which similarly glorified the destitute.

This psychological framework explains their fervent worship of “the Teacher” (教员) Mao Zedong, Che Guevara, and Thomas Sankara (a revolutionary Marxist-Leninist and anti-imperialist leader who, as president of Burkina Faso, launched a radical socialist transformation by nationalizing land and mineral wealth and rejecting Western neocolonialism). Their devotion to these figures is less an endorsement of a specific political agenda and more a resonance of martyrdom among losers. These idols were either crushed by the old order in their lifetimes or defamed by “capital” in the aftermath of their deaths. In these tragic heroes, the “Net Left” sees a reflection of themselves: they believe they did not lose because of a lack of ability, but because they were defeated by a fallen and degenerate world.

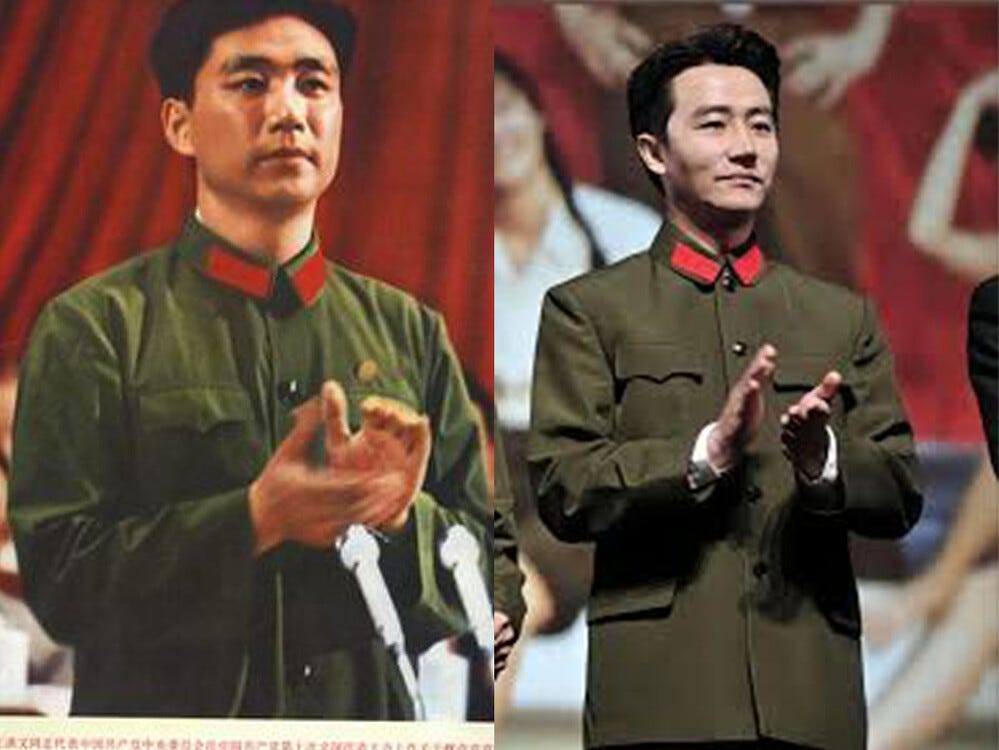

This psychology finds its most concentrated expression in visual culture, specifically a subcultural phenomenon prevalent among the “Net Left” which I call the “Wang Hongwen aesthetic.” In numerous Bilibili videos, users superimpose stills of actor Huang Xuan (黄轩) — who plays the protagonist Liu Feng in Fanghua — with historical photographs of Wang Hongwen. The core driver of this trend is the loser’s mentality discussed above. For the “Net Left”, Wang Hongwen is not merely a “worker prince” representing class mobility; he is a political projection of their own destinies.

These netizens interpret Wang’s downfall in the post-Cultural Revolution power struggle as the tragic failure of a proletarian representative besieged by “capital” and “elites.” This is mirrored by the fate of Liu Feng in the film, whose humble background eventually consigns him to the marginalized, sickly dregs of society in the Reform era. For the Net Left, Wang Hongwen’s failure is a badge of moral superiority—proof of a soul uncorrupted by “capital”. By empathizing with the vanquished, they recast their own stagnant lives as a narrative of tragic resistance. They romanticize the Cultural Revolution as a great era where workers held the powerful to account. For today’s young people, trapped in gig work, this imagery serves as a political shrine that dignifies their drudgery. Their yearning for this “great era” is a search for the only lens through which they feel politically alive.

The Structural Cause: A Distorted Market of Ideas

Prior to 2012, China’s public sphere was a place where “a hundred flowers bloomed” (百花齐放). On the newly emerging Weibo, individuals representing a vast spectrum of ideologies spoke freely. In an era before “like” buttons and recommendation algorithms, Weibo functioned as a digital plaza where divergent opinions congregated. For a moment, some felt that a Habermasian public sphere had finally emerged within an ancient empire that had restricted speech for centuries. However, history soon reverted to its normal timeline. Starting in 2013, Beijing began systematically re-tightening control over the free exchange of ideas, imposing official standardized answers for both current events and historical interpretation again. Any narrative deviating from these standards faced censorship or algorithmic throttling.

The narrative of the Cultural Revolution was no exception. Like all modern historical accounts in China, it had to serve a grander historical philosophy narrative introduced by Xi Jinping: “The Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation” (中华民族伟大复兴). For Xi, however, this may present an inescapable paradox. On one hand, the Cultural Revolution had long been officially designated as a ten-year catastrophe, a verdict he could not easily overturn — particularly given his own father’s persecution and public humiliation during that era. On the other hand, the image of the founding leader, Mao Zedong, had to remain absolutely infallible. Based on Xi’s “Two No-Negations” (两个不能否定) theory proposed in 2013, which posits that the post-reform era cannot be used to negate the pre-reform era and vice versa, any crack in Mao’s legacy would undermine the very legitimacy of the Communist Party’s claim to lead the nation’s rejuvenation.

To resolve this contradiction, the official answer to the Cultural Revolution became a sanitized compromise. While acknowledging it as a mistake, the state banned any criticism that deviated from socialist or communist ideology, labeling such dissent “historical nihilism” (历史虚无主义). Crucially, the authorities censored the most violent and brutal details of that era. The decade of turmoil was reframed as a mere detour or a period of national fervor under the supreme leader’s handwave on Tiananmen, scrubbed of the blood-soaked reality of the Chongqing armed conflicts (武斗) or the extrajudicial executions of the Chaoshan kangaroo courts.

This mosaic version of history, a correct memory of the Cultural Revolution with its gore and violence blurred out, unintentionally provided the fertile soil for the “Net Left” to romanticize the era. As moderate, reformist, and liberal criticisms were stigmatized as “historical nihilism” and purged from the public sphere, mounting social discontent and anger were forced to seek an alternative exit. These emotions eventually flowed into the only politically correct and safe outlet remaining: radical leftism.

While Beijing can censor Friedrich Hayek and Robert Nozick, and has even at times suppressed fundamental Marxism, it can never fully ban people from embracing the fundamentals of Maoism. Consequently, when the “Net Left” wields Mao’s Selected Works (毛泽东选集) to attack the current redistribution system and the bureaucratic apparatus, Beijing finds itself in an agonizing dilemma: it cannot suppress the very ideological foundation upon which its own legitimacy rests.

Learning from the failures of the liberals, the “Net Left” often avoids direct political expression, evolving a peculiar survival strategy: esoteric interpretation (suo yin, 索隐). They are obsessed with over-analyzing films and pop songs, digging for social critiques and hidden political agendas that the original creators may never have intended. To facilitate the spread of these interpretations among their peers, the student-led “Net Left” leverages its digital fluency to produce a vast array of memes and jargon. This cryptic language serves a dual purpose: it solidifies internal consensus and allows them to evade the prying eyes of censors.

Long before the Fanghua incident, Jiang Wen’s (姜文) 2010 film Let the Bullets Fly was the premier object of such esoteric obsession. The “Net Left” dissected the film and turned it into a political allegory of power transitions and people’s revolutions. They have mastered a specialized vocabulary of memes and slang derived from the movie, frequently applying them to interpret and critique contemporary reality. One particular line shouted by the protagonist (played by Jiang Wen): “Fairness, fairness, and still fucking fairness! (公平, 公平, 还是他妈的公平!)” became one of the most frequently cited quotes on various Chinese social media platforms. For example, Zhang Beihai Official, a prominent Bilibili content creator with nearly two million followers and known for his “Net Leftist” stance, frequently features this quote in his videos addressing injustice. In the eyes of the “Net Left”, these cultural products are no longer mere entertainment; they are codebooks for a clandestine political discourse.

To an outside observer, these esoteric interpretations appear far-fetched, even absurd. Yet, for the censorship apparatus, this very absurdity poses a formidable challenge. When critique and resistance are buried deep within the metaphors of a film or a song, the machinery of power struggles to predict which cultural symbol will suddenly be co-opted by radical youth. Even after a specific meme is banned, the “Net Left,” who can leverage the innate creative talent of the digital-native generation, rapidly discovers the next Let the Bullets Fly, packaging it into a new revolutionary totem.

Synthesizing these factors leads to a Frankensteinian outcome: the rigid regulation of the marketplace of ideas has forced social discontent to flow into the reservoir of fundamental Maoism. Individuals are arming themselves with the state’s most sacred ideological language, undergoing a radical reshaping within the blind spots of censorship through abstruse jargon. This posture of “waving the red flag to oppose the red flag” (打着红旗反红旗) traps the authorities in a paralyzing dilemma: they cannot easily suppress a movement that draws its breath from the very source of the party’s own legitimacy.

This provides another perspective on why contemporary Chinese youth have suddenly begun to yearn for the Cultural Revolution. They do not long for the actual, blood-soaked history, but for a political fantasy — one purified by a mosaic narrative and saturated with the colors of absolute equality and the smashing elites. In the face of rigid class stratification and the profound sense of failure felt by “small-town test-takers,” nostalgia for the Cultural Revolution has become one of the few legally viable means of resistance. They may not truly wish to return to the past; rather, they are using esoteric interpretation to re-narrate an old revolution to conduct a cross-temporal reckoning with the current order and redistribution system.

Weaponization of Emotion

The most unsettling aspect of this ideological trend is that it has completely transcended the realm of historical research and evolved into a form of identity-based political mobilization. For the “Net Left”, the actual historical granularities of 1966–1976 are irrelevant. Their emotional affinity for the Cultural Revolution is built not on historical facts, but on identity politics. By defining themselves as the “losers” and “dispossessed” of modern society, they have abstracted the Cultural Revolution into a perfect symbol of resistance: a mythic era where the marginalized could supposedly strike back against the established order.

Any attempt to persuade them with the grim reality of history is almost invariably futile. Within their internal logic, any fact that exposes the dark side of the Cultural Revolution is reflexively categorized as “elite smears” or “capitalist lies.” This immunity to facts has allowed the group to forge an extremely closed and radical ideological fortress. Beneath the surface, this represents a massive, high-pressure reservoir of angry energy.

Beijing has reason to fear the potent political conversion rate of this sentiment. In today’s highly digitized environment, this brand of identity politics can easily leap across geographical boundaries, instantaneously condensing isolated individuals — whether in the cramped cubicles of Tier-1 cities or the schoolrooms of underdeveloped rural towns — into a massive wave of public backlash. While this force is currently confined behind screens, it possesses the volatile potential to translate into offline action during a future social crisis. It carries a form of moral fanaticism rooted in the desire to reclaim “what was stolen.” Once this fanaticism erupts, its targets will not be limited to so-called “capitalists” but will inevitably clash with a governance system that finds itself unable to satisfy such radical demands.

It is worth noting that the discourse surrounding “small-town test-takers” is predominantly male-dominated. Young Chinese women rarely participate in or resonate with this topic. This is because, within traditional Chinese gender roles, women are typically not expected to shoulder material responsibilities; consequently, they face considerably less pressure than their male counterparts when confronting issues of unemployment and youth poverty. Even if some young women embrace feminist ideologies and distance themselves from these traditional gender roles, Chinese society itself has not abandoned these constructs. As a result, the intensity of stigmatization directed at unemployed or impoverished women is far lower than that aimed at the male population in similar straits. Ultimately, this leads to lower levels of pressure for women in these predicaments, and naturally, less resentment. Regarding the sexual anxiety implicit in the “small-town test-takers” narrative, Chinese women have long been socialized to suppress their sexual desires. Even for radical feminists, the unique yet popular East Asian “4B6T” feminist movement (no marriage, no childbirth, no dating, and no sex) is inherently a form of suppressing sexual desire. Therefore, women rarely respond to the sexual anxiety dimension of this discourse either.

While a radical anarchist-leaning faction exists (led by Bilibili streamer Wei Mingzi, 未明子), the majority of “Net Leftists” are “loyalists.” They distinguish between the Party’s Central Committee, which they view as inherently good, and a corrupt lower bureaucracy aligned with capitalist interests. In their narrative, Xi Jinping is leading a difficult crusade against these interests, which are seen as a formidable, “deep state” enemy within the system.

Given the many resonances with similar phenomena in the U.S., particularly on the right, neither censorship nor anything specifically Chinese or communist seems to be the fundamental cause. Human beings seem to have an endless ability to project their longings onto periods in the past, obscuring their horrors in the process. Glamour is a powerful form of rhetoric, and a dangerous one (says the author of The Power of Glamour, also available in Chinese).

Very good narrative and analysis. As a Chinese I am constantly confused and worried by the censorship we have in terms of publications.

Just by the way, this post is interestingly coherent with an episode of Bumingbai Podcast (不明白播客). Do you know each other by any chance?