Notes on Kyrgyzstan

Lily Reports!

Kyrgyzstan is Central Asia’s island of democracy…relatively speaking. As a mountainous, landlocked state without oil or gas endowments, the country faces a difficult development path. Yet, Kyrgyzstan’s GDP has grown at a rate of 9% every year since 2022, and unemployment recently reached a record low of 1.6%. In the capital city of Bishkek, there is an air of optimism, national pride, and commitment to economic growth of the sort I’ve only ever felt before in Poland — and partnerships with China are an important part of that story.

This month, I (Lily, ChinaTalk’s lead editor) spent some time exploring Kyrgyzstan and speaking with locals about Chinese influence in their country. Here are my reflections.

Setting the Scene

Bishkek is a green city full of trees and flower gardens. The preferred colors for front doors and other infrastructure seem to be sky blue and sea foam green, which complement the natural landscape nicely. An exception to this trend is the fleet of “Comfort”-class taxis, which are pale orange models purchased from Korea. The summer weather is mild, and the parks are full of little children laughing and enjoying the long days. Most restaurants have super comfortable chairs with thick, bouncy cushions.

Possibly my favorite thing about the city is the abundance of 24/7 flower shops — you know, for when your event needs a midnight flower supplement, or when you need to prove your dedication to a dance partner with a bouquet.

China x Kyrgyzstan

In Kyrgyzstan’s largest cities, Bishkek and Osh, there are construction sites everywhere, usually operating with Chinese or Korean equipment, and often financed with Belt and Road loans. Notable works in progress include a new transnational highway, regional airports, a BYD factory, and the largest ski resort in Central Asia (opening winter 2026!).

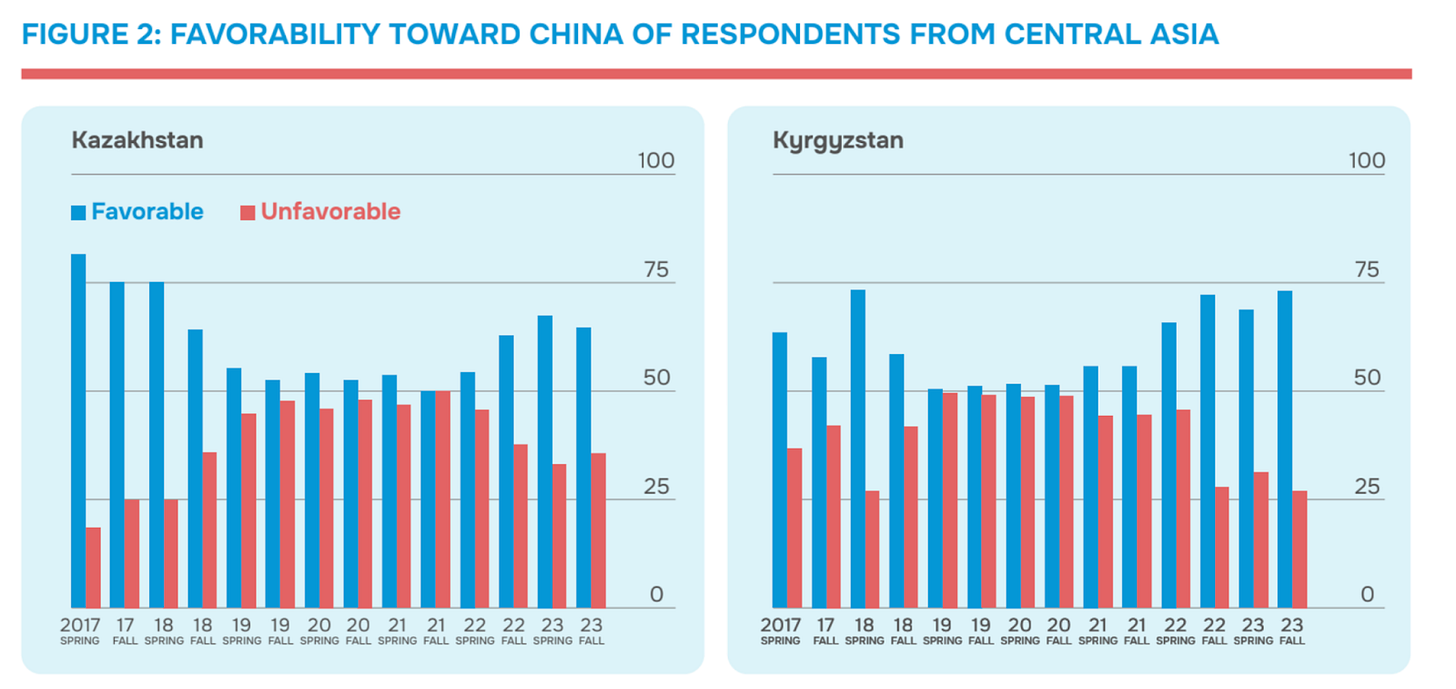

After Kyrgyzstan joined the BRI in 2013, opinion polls year after year showed that Kyrgyz people were skeptical of China’s economic influence, though they welcomed economic engagement with Russia, their former colonizer. That began to change in 2022 — positive feelings toward China proliferated rapidly in the booming post-pandemic economy. By 2023, a large majority of the Kyrgyz public supported new Chinese investments in their country, according to polling conducted by the Central Asia Barometer. Those surveys (as well as Gallup polling) indicate that educated people and individuals with higher incomes are especially favorable toward China, a trend that also held in neighboring Kazakhstan.

This data indicates that people are seeing, or expect to see, real benefits from dealing with China. Already, the Ala Archa National Park has its own fleet of Chinese-made electric buses to shuttle hikers into the park, and the city of Bishkek has purchased hundreds of Zhongtong buses from China in the hopes of reducing traffic jams and air pollution.1 (This is a noble effort, but traffic is still quite bad. What Bishkek really needs is a metro.)

Still, even as people support Chinese investment, trade, and technology, they continue to feel negatively about Chinese workers in their country. To make sense of this disconnect, we have to understand that Moscow bombarded Central Asia with propaganda about a looming Chinese invasion for decades following the Sino-Soviet split. Remember that there was active combat on the border between Kazakhstan and Xinjiang during the undeclared 1969 Sino-Soviet war.2

The Kyrgyz government caps work permits for foreigners at about 15,000, and 75% of these permits go to Chinese workers. That doesn’t sound like much, but to quote Bruce Pannier of Radio Free Europe, this represents “the biggest influx of an outside group since independence.”

Three protests against Chinese laborers broke out in Bishkek between December 2018 and January 2019, incited also by the news that the Chinese government was detaining ethnically Kyrgyz people in Xinjiang.3 While only around 500 people attended the largest of these protests, the unrest sparked a national conversation when 21 protesters were arrested.

In the months following the protests, government officials worked to dispel anti-China sentiment in preparation for a state visit by Xi Jinping, including by speaking to the press about the protests and publishing evidence disproving rumors of mass illegal immigration (and of Chinese leftover men seeking Kyrgyz brides). In the words of Carnegie’s Temur Umarov, Central Asians “don’t fear China per se — they fear that their own elites are not loyal to the national interest, but loyal to their own cynical interests.” Today, sentiment surrounding Chinese immigrants is improving, but their favorability is still underwater.

In Central Asia, Belt and Road projects are mostly staffed by local people. Apart from the cap on work visas, imported Chinese labor is far more expensive than hiring locally. Instead, Chinese immigrants mostly work in technical or managerial roles, where they oversee and, crucially, train large teams of Kyrgyz employees. So, the vast majority of China’s economic impact in the region comes in the form of completed infrastructure, employment opportunities, and cheap consumer goods — not from the presence of Chinese people on the ground. As Chinese companies increasingly outsource operations to cheaper pastures, Belt and Road investments represent a platform for future business partnerships.

The Chinese workers I met in Bishkek had come to Kyrgyzstan to mine precious metals, to open restaurants, or to import Chinese goods to sell at local markets. (I visited three of these markets — Dordoi, Osh, and Madina. Dordoi was my favorite by a wide margin.) None of the Chinese people I met could speak Russian, much less Kyrgyz.

The Chinese food I had in Bishkek was pretty good, as far as international Chinese food goes. Upscale Chinese restaurants are quite trendy, usually serving photogenic versions of classic dishes with a local spin. There are also more authentic Chinese restaurants where the vast majority of customers are Chinese immigrants.

Travel Notes

Central Asia has disproportionately high fertility for its level of development. Some people attribute this to increasing religiousness after the fall of the Soviet Union. Anecdotally, I didn't observe mothers covering their hair at a higher rate than the general female population. In any case, large, close-knit families are culturally the norm and Kyrgyz weddings usually have 500-1000 guests!

Physical fitness seems really important in the national consciousness. I arrived on the same flight as the Kyrgyz national wrestling team, who were returning from an international competition and were welcomed by hundreds of people at the airport at 5 am. The national sport is kok boru, which is like soccer, except instead of kicking a ball into a goal, the players ride horses and compete to throw a 90lb (40kg) dead goat into an elevated pit.

Grocery stores sell a truly staggering array of sweets, as well as a diverse range of dairy and meat products. They don’t offer many fresh vegetables, but there is usually a counter where you can order tasty premade salads. My favorite was the “Caucasus salad” that comes with beef.

I spent a week in Bishkek, which wasn't nearly enough time to explore all the beautiful landscapes and historical sites around the city. My favorite excursion was a hiking trip to Konorchek canyon. I had a fantastic guide named Chinggis (who is now ChinaTalk’s second listener in Kyrgyzstan) — I laughed, I cried, and learned a ton about Kyrgyzstan’s democratic revolutions! People in general were so friendly and helpful, and they seemed to really care whether I was having a good time in their country. They even complimented my Russian skills — which never happens when I’m talking to Russian people.

Finally, Kyrgyzstan is very good at sunsets. Here’s my favorite:

Zhongtong makes buses for a huge variety of locations, including Argentina, Singapore, Germany, Indonesia, and the UAE.

The feeling of this propaganda is epitomized by an old Soviet joke about Chinese military strategy, where troops plan “to cross the border in small groups of two to three million” (Переходить границу мелкими группами по 2-3 млн).

After imperial Russia violently put down the Central Asian Revolt of 1916, hundreds of thousands of Kyrgyz and Kazakh people fled to China to avoid being conscripted to fight in WWI.

Very nice post! I was in Kyrgyzstan a few weeks ago and thought it was very nice

Nice review! I visited this time last year.

I loved visiting the Dungan (东干) people in Karakol. They arrived in Kyrgyzstan in the late Qing. They still speak a Shaanxi dialect (I could understand maybe 40%), but can't read Chinese characters. They even had books of folk tales written in Cyrillic that they could read in their dialect. It kind of felt like visiting a China that no longer exists. Also made me realise how rare it is in the mainland to hear young Northern dialect speakers who don't speak Mandarin.