The Myth of China's "AI Talent Pipeline"

Life inside the "human sea attack"

Zilan Qian is a program associate (research) at the Oxford China Policy Lab and holds a Master’s degree in Social Science of the Internet from the University of Oxford.

Trigger warning: the second half of this article explores suicide.

“The US-China AI race is a race between Chinese — those in the US vs. those in China.”

This joke has real-world references. It is no secret that Chinese engineers and researchers make up a meaningful percentage of the AI workforce in the US. According to the Paulson Institute’s Global AI Talent Tracker 2.0, by 2022, US institutions relied more on Chinese AI researchers (38%) compared to US AI researchers (37%). Yet, this tracker still underestimates the Chinese AI talents in the US, because researchers are only counted as Chinese if their undergraduate degree is from a Chinese institution. That excludes a massive number of China-born AI researchers who did their undergraduate degrees in the US.

Meanwhile, China’s own AI progress, almost 100% powered by China-born Chinese, has grown at an unmatched pace. Besides the industry performance that can compete with the US, in 2024, China’s AI research publication output matched the combined output of the US, UK, and European Union, and now commands more than 40% of global citation attention.

People often cite China’s talent pipeline as one of its most valuable strategic resources — a system to admire or even emulate. Unfortunately, this view is fundamentally wrong. The system is highly inefficient, with a low cost-return rate: the top STEM genius everyone sees at the summit is built upon the bodies of massive numbers of talented students who failed to reach the top.

This piece is not about the life stories of successful Chinese AI or STEM talents. It is not about how the talent system works — but about how it does not. It explores the price paid to create this talent pool and the untold mental health stories behind it, as experienced and witnessed by me.

How to Build an “AI Talent Pipeline”

I grew up in Hangzhou, which is known today as one of China’s booming AI and robotics hubs. I went to some of the city’s top middle and high schools, the kinds of places that sit at the center of the country’s STEM pipeline. A middle school senior several years ahead of me became the co-founder of xAI, and another high school senior cofounded Pika AI.

My high school reliably produces at least one International Olympiad gold medalist in STEM subjects every two years, and a recent student just outperformed OpenAI in the International Olympiad in Informatics (IOI). All except one of my high school classmates majored in STEM, and about half of them went on to Zhejiang University (ZJU) — the alma mater of DeepSeek’s CEO. A handful of my friends are doing PhDs in CS, EE, or ML at leading Chinese and Ivy League-level overseas universities, some supervised by professors listed on Times AI 100.

On paper, this is the kind of pipeline many places dream of building. In practice, living inside it felt far less enviable.

In elementary school, most parents enrolled their kids in Olympic math training. Some of my peers juggled six different math tutoring classes a week. Later, these math programs began to lose popularity, replaced by coding, Python, and machine learning courses. By the time I entered middle school, coding had become a standard path.

Before the first day of middle school, the school coding team held a 2-hour math exam to recruit new members. Out of 650 students in my cohort, more than 100 were selected for the first round. Over the next two years, that number shrank to about 15. At first, we trained for half a day a week, later a full day. This came on top of 7 am-to-5 pm schooldays (which would eventually stretch to 7 am-to-9 pm, 5.5 days a week) and weekends packed with supplemental classes.

The reward was clear: perform well in provincial programming competitions and you could secure a spot in a top high school. The risk was equally clear: most students could not balance this with preparing for the high school entrance exam, and eventually lost both the opportunity to enter a top high school through programming competitions and the regular path through the high school entrance exam (高中招生考试, which is usually known as 中考). In my city, 95,000 students sat for that test each year, and my high school (the top 1 in the city) recruited less than 300 through exams (and another 300 through other means).1

High school further raised the stakes. Prestigious schools ran Olympiad teams in math, informatics, chemistry, physics, and biology. At my school, at least 400 students entered these training streams, but fewer than 30 students in total might reach the national stage representing the province. There, fewer than 5 in total get selected into the national team and advance to international competitions. At the peak of the system, winners of international and occasionally national competitions were guaranteed admission to Peking or Tsinghua University, while reaching the national stage may get certain admission priority compared to others in the Gaokao. In 2022, the admission rate of Peking and Tsinghua combined in Zhejiang Province was 0.16%.

The training often began with one day per week and escalated to full weeks or even months devoted entirely to Olympiad preparation. Meanwhile, boarding school meant a 6 am-to-10 pm schedule, with Sundays spent back at school by noon and weekends set aside for extra classes. For those who fell behind, catching up to peers who had been preparing for the Gaokao full-time was almost impossible. The later you were eliminated from the Olympiad track, the more closing the gap and getting into a good university via the Gaokao became a hopeless endeavor.

If you do make it past the Gaokao, the grind continues in university. A friend at Zhejiang University once told me that during exam months, she slept only three hours a night. In her dorm, six students rotated sleep so that someone was always awake to wake up the others after their allotted three hours.

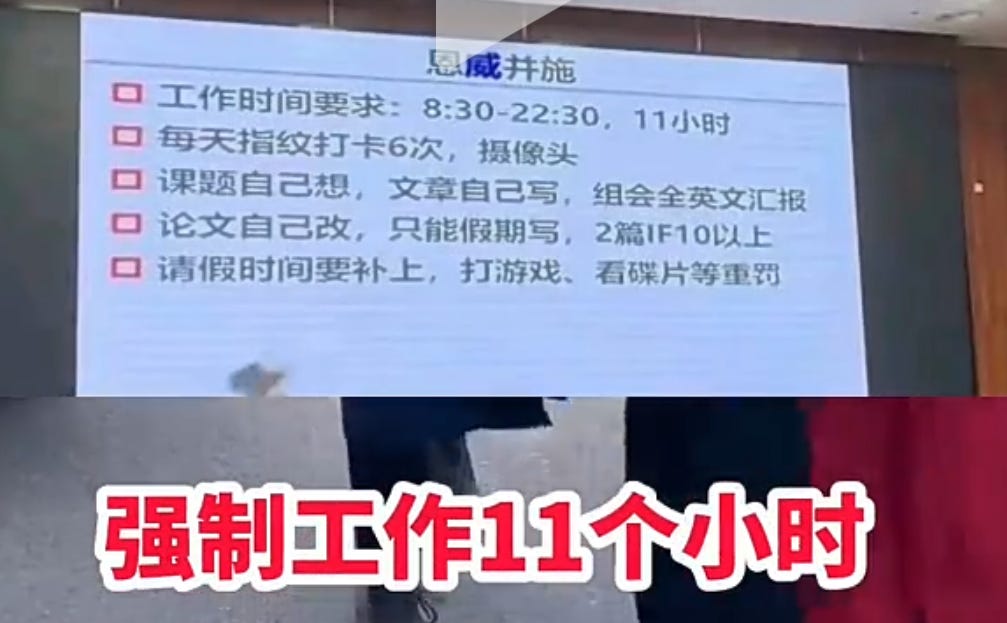

If one is to continue in academia in China, metrics for academic publications create mounting pressure. To obtain a CS-related PhD from Zhejiang University, students are required to publish at least two articles in SCI as the first author, and at least one needs to be in a CAS Zone 2 journal (at least the top 15% of the respective discipline). Other universities have similar publication requirements. And for those who stay in academia, the pressure only intensifies! China’s 非升即走 (“up or out”) tenure system sets strict timelines for publications and funding, with no second chances for those who fall short.2

Across all these stages, the structure looks less like a ladder of opportunity than a staircase with a trap door at every step. Each milestone comes with an award for the top STEM students–admissions priority — but also punishes those who fail.

And there is no cushion for failure. If you fail to get into a good middle school because you split your time between coding camp and the high school entrance exam, you have very little chance of getting into a good university. The scarcity of resources means that at a mediocre high school (meanwhile, around 50% of middle schoolers do not even get into academic high schools), you would have no chance of getting good STEM coaches and support to continue exploring your talents in high school.

The other door to good universities — taking the Gaokao — is also closed to most, if you cannot get into good high schools. The best two high schools in my city each sent more than 140 students to the best university in my province (Zhejiang University) in 2024 (and more than 40 each to Peking and Tsinghua Universities). The 10th high school (which is still considered good in academic performance) sent 19 students, whereas most schools ranking below that had single-digit or no admissions.

Meanwhile, an average university does not offer great resources for its STEM students. The 2021 Nature study shows that a Chinese STEM student’s university experience is a high-stakes filter. While only students in elite institutions achieved significant growth in critical thinking and academic skills over four years, the average STEM student at a non-elite university saw virtually no skill gains and often experienced a decline. This stagnation is particularly notable because these average Chinese students begin university with skills significantly surpassing those of even top students in peer countries like India and Russia. Their considerable initial talent is thus arguably wasted because the Chinese system reserves the resources necessary for continued skill development exclusively for the small cohort admitted to the most selective, “elite” institutions.

This is a system of ruthless natural selection: only the brightest continue, and the rest are quietly discarded.

The Human Cost of Building the STEM Talent Pipeline

Trigger warning starts here…

In the autumn of 2018, I was waiting at a psychiatry clinic to address my burnout problem after preparing for the Gaokao and the SAT at the same time. Suddenly, the machine voice called out a familiar name: a high school classmate from the Olympiad team. Teachers had described him as a future national champion, someone destined for Peking or Tsinghua and top national science labs. We saw each other in the waiting room but did not speak. The silence was an agreement to pretend we did not know each other.

Mental health was rarely spoken of openly, but the signs were widely available. I knew many classmates whose middle or high school experiences left visible or hidden scars. One had long marks on her arm from self-harm. Another took a gap year halfway through high school. A few transferred to middle/high schools abroad. Three more took gap years later, during their university studies overseas.

All of them were once the students that teachers and parents placed the highest hopes on — top of the class, members of math or informatics Olympiad teams. Yet few became the “talent” they were trained to be. Many ended up in very good places — Oxbridge, the China Academy of Art, consulting, or finance — but not in the elite Chinese labs or international research institutes that had once seemed their destiny. These alternative paths offered equally sustainable futures, often at a lower personal cost, particularly for those with the economic or social resources to pursue them. But they were not outcomes you could announce proudly among peers. Foreign degrees, artistic pursuits, and wealth were desirable — but they were secondary to being regarded as exceptionally gifted in STEM and proving yourself through your own intellect, specifically inside the traditional ivory tower.

However, not everyone is lucky enough to find a path and make it through. During the 2020 Gaokao year, with Covid-19 disruptions compounding the stress, there were at least three high school students rumored to have committed suicide in the city. None were publicly acknowledged. Local schools, authorities, and media downplayed the incidents.

When I returned for a middle school reunion last year, one teacher told me there are now “one or two cases [of students committing suicide] every semester” in the city. My friend, who is beginning a PhD in CS at the best provincial university, said his department had two student suicides in 2024.

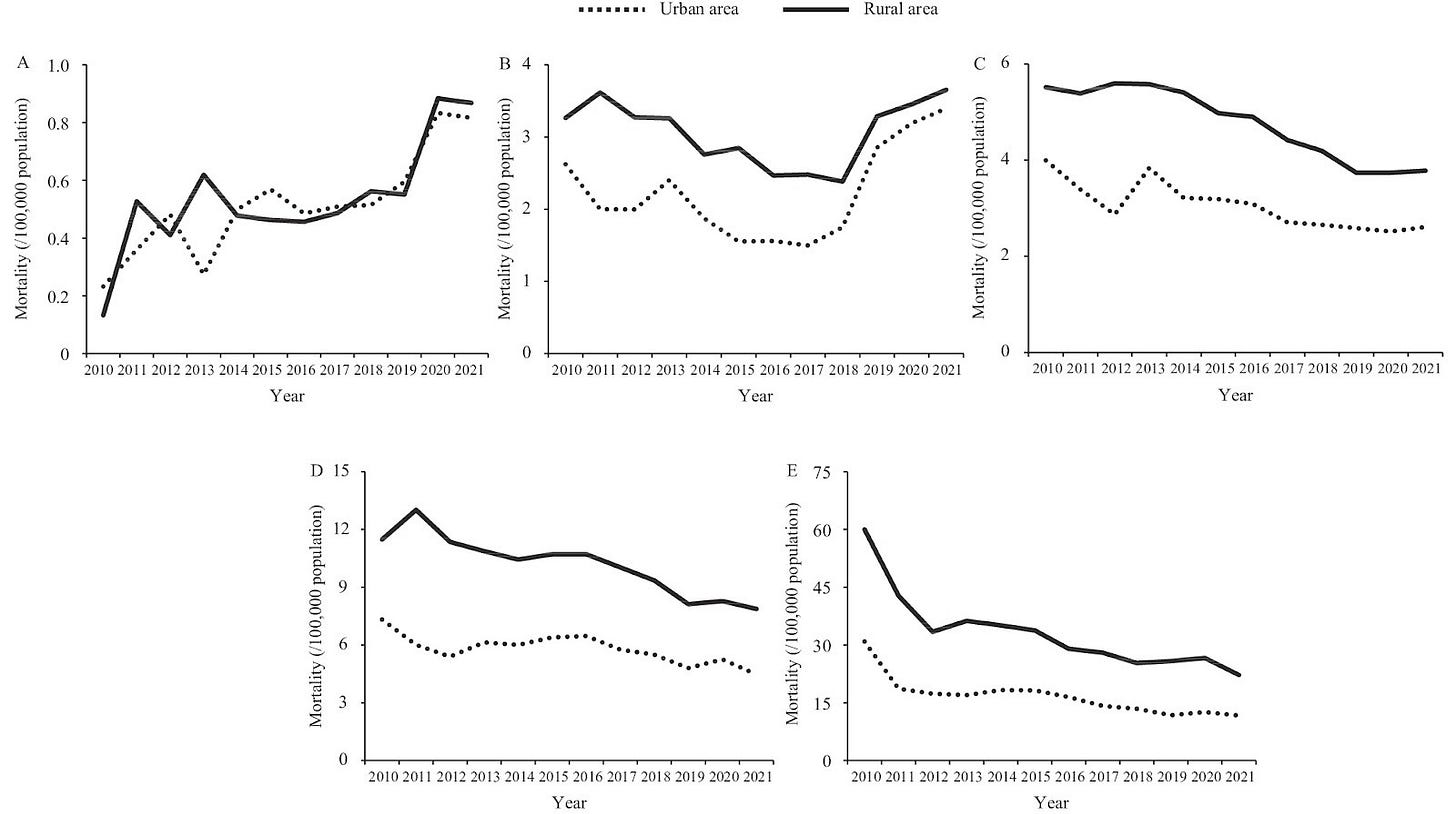

Even public data confirms the trend. A 2023 study published in the China CDC (Center for Disease Control and Prevention) Weekly 中国疾病预防控制中心周报 reported that while overall suicide rates in China have declined, the rate among children and adolescents has risen. Between 2010 and 2021, suicide deaths among urban and rural children aged 5-14 substantially increased, as did deaths among 15-24 year-olds from 2017 to 2021, surpassing three per 100,000.

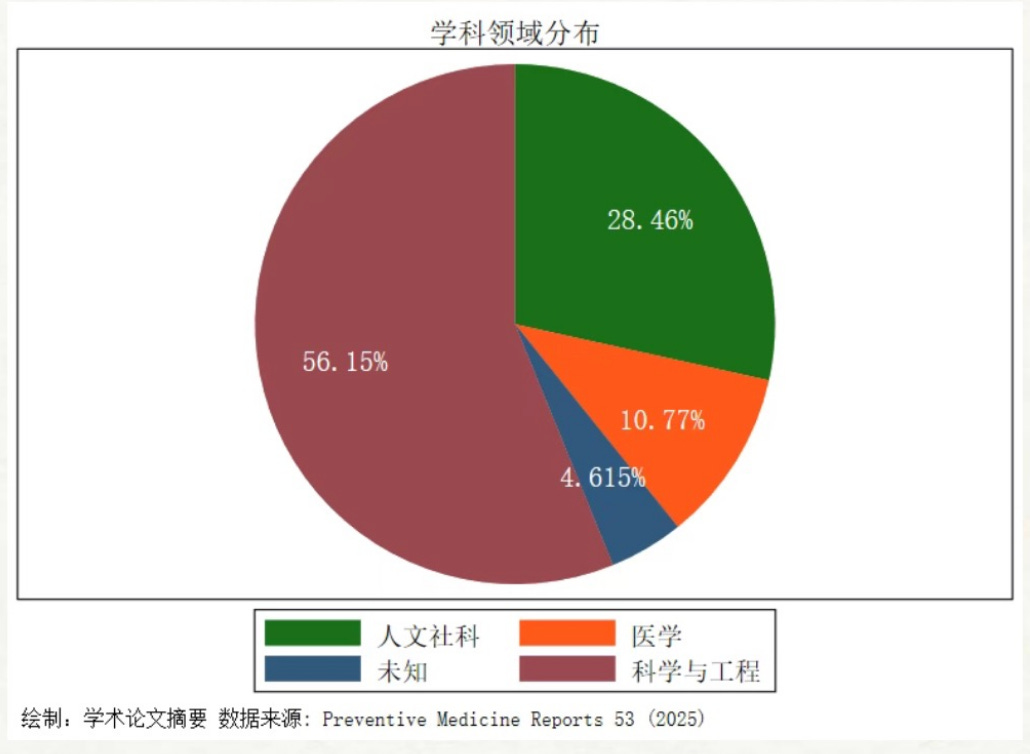

However, the pressure is not limited to students. Young academics, especially those working in STEM, also struggle with mounting research pressures. A 2025 study compiled 130 verified suicide cases in China’s academic and scientific circles from the 1990s to 2024. It found that work and academic pressure were the leading factors, cited in 53 percent of cases. More than half of those who died worked in science and engineering fields. The most affected age group was 20-29, accounting for 53 percent of cases. And the numbers are rising: 38 cases were recorded from 2000 to 2009, 52 from 2010 to 2019, and already 38 between 2020 and 2024.

How to Hide the Cost

The figures above almost certainly underestimate the problem. They capture only the cases that slip through layers of silence. Suicide in China’s education and research system is managed through a multilayered regime of suppression.

At the first level, teachers (for student suicides) and school administrators downplay or conceal incidents. Their incentive is straightforward: avoid public criticism and protect their own careers. Local governments then step in to prevent negative publicity, leaning on media outlets and social platforms to delete or bury reports. If those measures fail, the central government becomes involved, concerned primarily with preserving social stability.

To be fair, investigations can be carried out at each stage. Teachers and schools usually notify local police; the education bureau may research the cause of suicide, and the central state would also mandate a more thorough investigation. There are many cases where public attention was enough to push for good investigations and the central state’s public acknowledgement. But many more cases do not survive until that stage, and investigations often leave room for more speculation.

For example, when a 17-year-old boy suddenly fell to his death in his high school in 2021, school administrators swiftly seized his body and drove to the funeral parlor, while notifying his mother only two hours later and banning her from entering the campus. Meanwhile, local police aggressively censored posts on social media and blamed the death on a “personal issue.” Although public dissent was large enough to force a central authority-mandated re-investigation, local police again ruled out foul play and claimed the family had “no objection.”

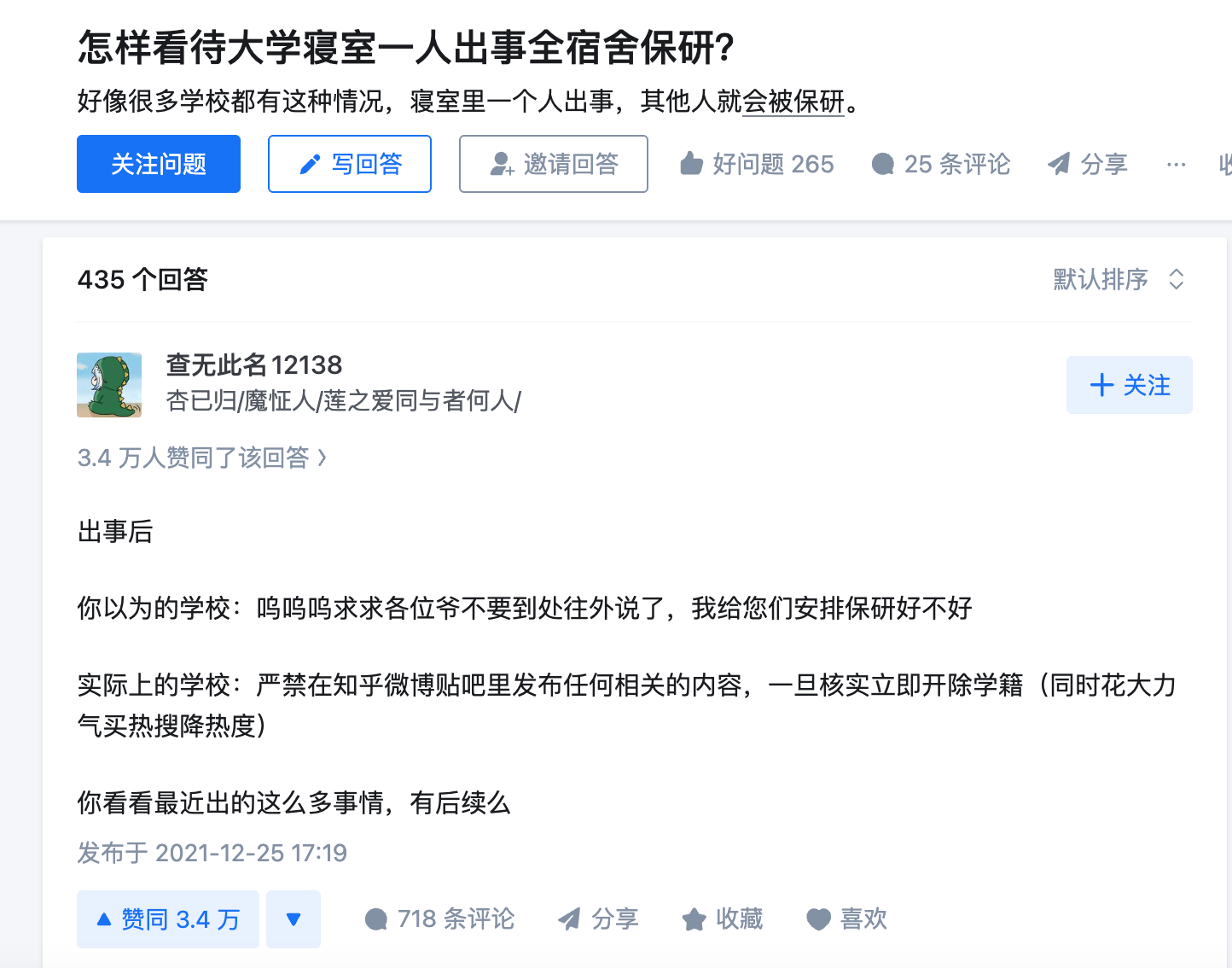

Some students make dark jokes that the only way to guarantee graduate school admission (保研) is if your roommate suffers something life-threatening. In cases of rape or suicide, some universities quietly offer guaranteed admission to those who report the incident, so the case doesn’t become public. The humor is bitter, but the logic is rooted in lived experience where tragedy is normalized, even instrumentalized, in a system that prefers silence to awareness and change.

This censorship compounds the stigma already surrounding mental health. Seeking help is seen as wasting precious study time. Shame still lingers around mental health despite some recent improvements in awareness.

The Collective “Dream”

What do I see as the secret of China’s AI talent? A “human sea attack 人海战术”: massive scale creates fierce competition that elevates top performers, while accepting enormous attrition as the system’s operating cost. Enough talented students enter the pipeline that losing most along the way still produces exceptional outliers at the top.

But scale and attrition alone don’t fully explain the system’s output. There was also an ideological component. After I left China to study abroad, I met many students from Oxbridge and the Ivy League. Many are very smart, but probably few of them could compete with my Chinese classmates within the Chinese system. The elite students in the UK and the US were brighter in another way — passionate and determined as individuals.

Meanwhile, we had been taught to be passionate and determined as a collective.

“Though hardships endure, never cease striving forward, with utmost loyalty in service to the nation; 忧患其久 不辍奋进 精忠报国. Only seeking great achievement, to pass on the torch, for future generations to rely upon. 唯求大成 薪火相继 后学所凭.”

These lines come from my high school’s school song. Back then, studying STEM carried an implicit patriotic mandate — the ideal was to become a pure scholar advancing the nation through knowledge. This was the greatness we were all supposed to be pursuing, the torch in our hands, and the shared future into which we were meant to channel our passion.

Of course, this patriotic mandate is different from the one China had decades ago. The years of pure scientism and old scientific nationalism in China have faded. Many students now consider practicality over ideology, choosing economics or finance over foundational sciences, to the extent that the state started to censor such narratives as negative emotions. Mental health awareness has grown. Overwork is no longer universally celebrated as dedication to the nation.

Yet the embedded ideology of techno-nationalism, or — in the parlance of modern propaganda — “science and education for the development of the nation” (科教兴国), remains powerful for individuals, especially when geopolitical pressures reinforce it. Regardless of whether ordinary Chinese think they are racing with the US, many of us have been trained to race, especially in STEM, from the very beginning of our lives.

The core question about China’s talent system is not whether China can continue producing top AI talent through this system. It can, at least until its population shrinks drastically. It is not whether other countries can have as many native talents as China has — they can, if they have enough people to lose. The question is whether we have paid enough for this race, and whether the next generation will be willing to pay more — both racing internally against each other, and externally against other countries.

The high school’s alternative recruitment drive brought in 300 additional students via two main channels: test-waived admissions (保送名额) for the top 1-10 students in feeder middle schools, and separate provincial exams (省招) to secure top STEM talent from high schools in neighboring counties.

Historically, Chinese academics enjoyed more permanent “iron-rice bowl” 铁饭碗 style employment without these formal up-or-out reviews. However, many Chinese universities now operate a fixed-term “tenure-track” system: junior faculty (assistant professors or post-docs) are given roughly six years to meet strict criteria—mostly around publications and grants—and then either receive a permanent (tenured) appointment or leave the institution.

The system resembles the US tenure track, where junior faculty undergo a six- to seven-year review. However, in the US, meeting the evaluation criteria is generally sufficient to secure tenure. Except in a handful of elite institutions, faculty in American academia are unlikely to be denied tenure at the end of their review periods, and elite-school tenure-track scholars generally have flexibility to move to other institutions. Whereas in China, simply fulfilling the metrics set by the university is often not enough. Candidates frequently need to exceed expectations by a significant margin, which has led some to describe the process as a tournament, with multiple rounds of competition to secure a position. Others characterize China’s tenure system as a “bet-on agreement” (对赌协议) between the individual and the university: if the researcher succeeds, they gain tenure and its associated benefits; if they fail, they may lose their position entirely and, in some cases, be required to repay relocation or housing subsidies.

Great article Zilan. This was such a moving and sobering read. It captures so well that mix of ambition, exhaustion, and fear that defines so much of elite education and tech work in China. It left me both grateful for your 'from-the-inside' perspective and deeply sad for what it costs.

Insightful article! It demonstrates why China has been advancing as fast as it has been.

I’m not sure the suicide level is due to academic pressure though.

According to the CDC, the suicide rate for 15-24 year olds in the US is about 4 times higher than China’s, and unfortunately, academic performance in the US seems to be at an all time low.

I think social factors have a more significant influence on young people.

https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/data.html