Top 10 Books of the Year of the Snake

Happy new year everyone!

Some essays I want to write at some point include

How corruption in China compares to corruption in American politics

Why Bruce Catton’s The Potomac Army series is better than Robert Caro’s LBJ saga

Deep dive into the writing in Ian Toll’s The Pacific War series and how he sets up scenes and transitions from individual engagements to strategic dilemmas as smoothly as I’ve ever read

Over paternity leave I read ten different books on the theme of “oh I raised my kid in X country here’s what it was like”. I could compare and contrast, tier list countries…

Vote for what you’re interested in in the comments?

Top Ten

Religion

Genesis, Exodus, and Prophets.

After a lifetime of reading the torah in bits and bites, dutifully reading footnotes and commentary, this year I tried a new tack with an audiobook bible binge, listening straight through first the Robert Alter and then the King James Bible. Alter feels deeply foreign and startling while KJB’s language gently washes into you. The plotblast in Genesis can be overwhelming but this experience helped my brain refocus away from my natural default of specific verses and word choice and towards broader arcs.

Bob Thurman’s Jewel Tree of Tibet (audiobook) + Circling the Sacred Mountain

Donald Lopez’ Buddhism: A Journey Through History and The Buddha: Biography of a Myth were fantastic intros but the Buddhism books this year that left more of an impact were Robert Thurman’s. His Jewel Tree of Tibet lecture series puts Headspace to shame. This book, a combination of guided meditation and lectures best enjoyed via audiobook, gives a sense of just how strange the Tibetan cosmology is and allows you a taste of it yourself with his Lake Manasarovar visualization. Falling asleep to random episodes of his podcast leads to weird and wonderful dreams.

Circling the Sacred Mountain is a travelogue with paired narrations to a trip to Tibet in the 1990s. One is the enlightened Robert Bowman, the other an annoying hanger-on whose experience is very skippable. I felt the blade wheel of mind reform.

He also does some superb phrase translations, like Superbliss-Machine Embrace (Buddha Paramasukha Chakrasamvara).

Now recall the three roots, finding the points that make the most sense to you: that death is a certainty; that the time of death is completely unpredictable; and that nothing of this life will translate into the next except what enlightened qualities you have attained. Give up all of your mental and physical possessions, the body that you identify with as your self. Your soul will proceed into new forms, guided by imprints of generosity and morality, tolerance, enterprise, concentration, and intelligence — the opposite of stinginess and fear and paranoia. Forget about the peripheral things. You will go forth with your luminous soul, your sea of infinite bliss, your buddha-nature, so build up that subtle deepest part of yourself.

War Section

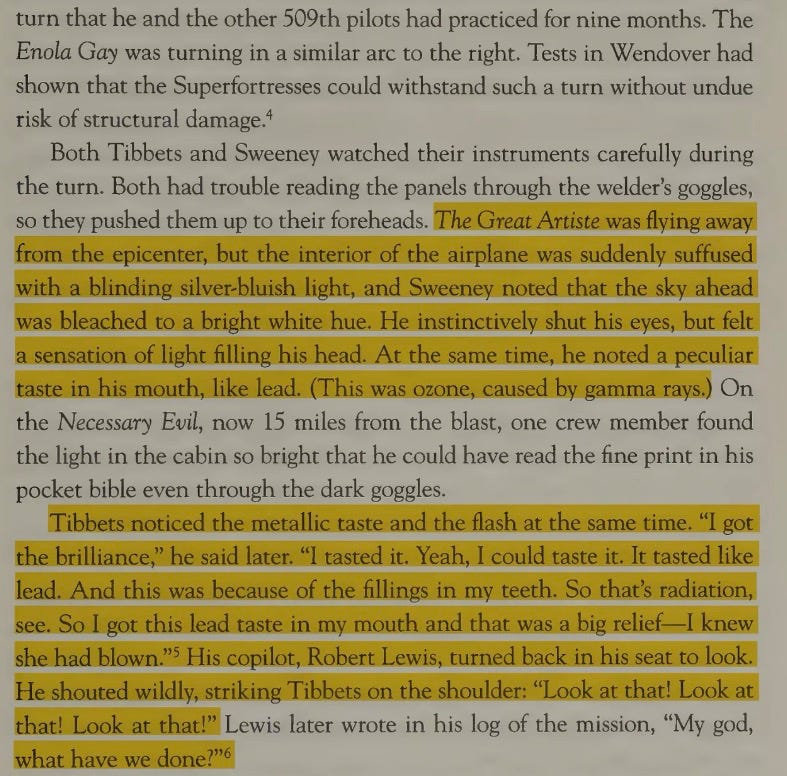

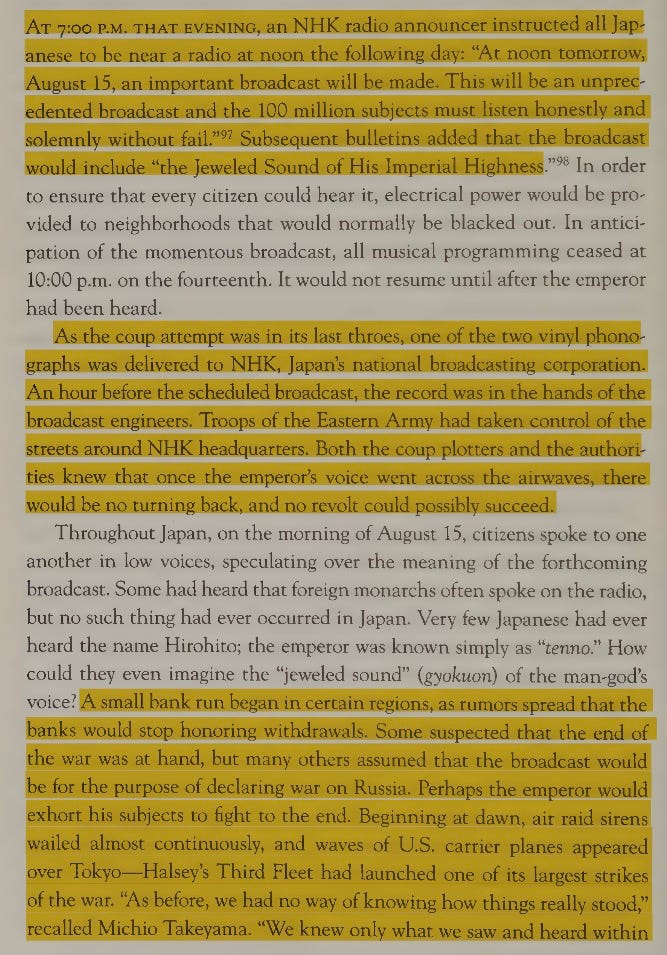

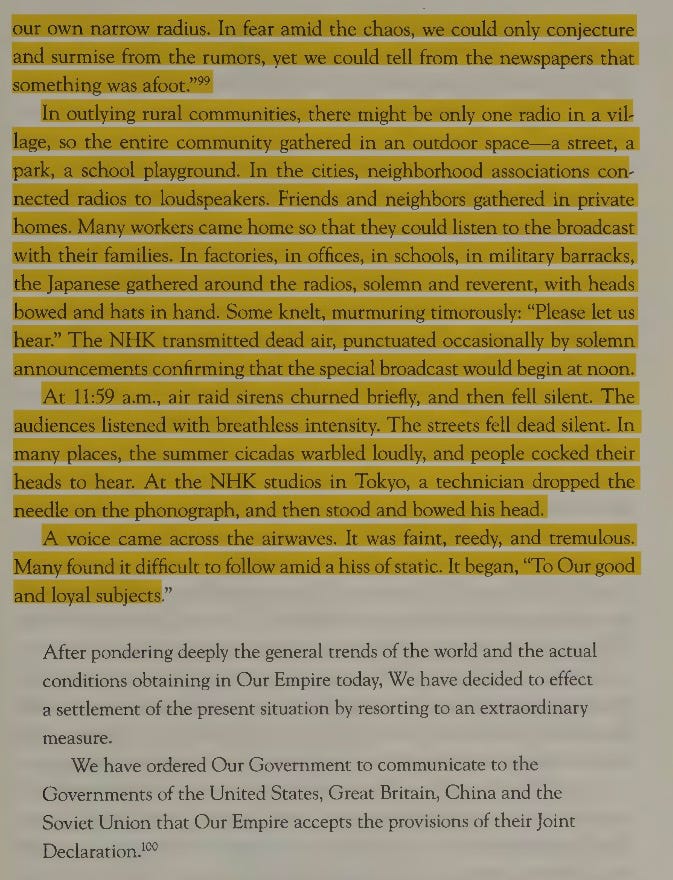

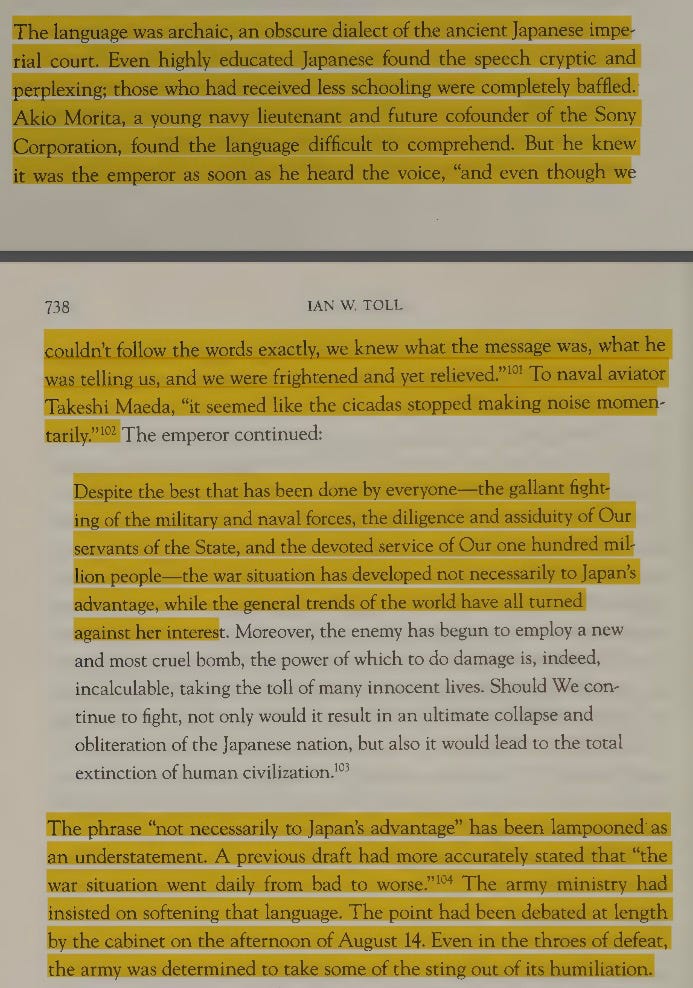

Ian Toll’s Pacific Theater WWII trilogy is a modern masterpiece of writing and scholarship. The third book is the strongest, thanks to the drama of the material and Toll’s maturation as an historian over the fifteen years it took to produce.

His chapters to bookend the series are some of the best I’ve ever read. He opened with Admiral Nimitz taking a cross-country train from DC to SF on the way to Pearl Harbor, meditating on the national mobilization and the burden he was about to adopt. The closing climax of Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the decision to surrender, takes the reader from the Truman to the Enola Gay, to the Emperor recording his surrender, a military coup trying to stop the broadcast only for Japanese to hear it across the country is also a masterpiece.

A few masterful pages on the recording and reception of the famous surrender broadcast.

Covered in podcasts here and here.

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, Hannah Arendt, 1963. I would have read this years ago if anyone told me how funny it was! As she wrote to a friend, “You are the only reader to understand what otherwise I have never admitted—namely that I wrote Eichimann in Jerusalem in a curious state of euphoria.” It shows and is so much better for it.

World-historically funny.

Extended excerpts here in my Tel Aviv writeup.

Communism

The Party’s Interests Come First: The Life of Xi Zhongxun, Father of Xi Jinping, Joseph Torigian, 2025. A China book at the level we get only a few times a decade. A true must read for anyone hoping to deeply understand the CCP and Chinese 20th century history. Covered in a podcast here.

Cancer Ward, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, 1968.

The Gulag Archipelago, Vol. 1: An Experiment in Literary Investigation, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, 1973. Survivor and stylist. Energy and humanity sparks though the prose.

Look around you—there are people around you. Maybe you will remember one of them all your life and later eat your heart out because you didn’t make use of the opportunity to ask him questions. And the less you talk, the more you’ll hear. Thin strands of human lives stretch from island to island of the Archipelago. They intertwine, touch one another for one night only in just such a clickety-clacking half-dark car as this and then separate once and for all. Put your ear to their quiet humming and the steady clickety-clack beneath the car. After all, it is the spinning wheel of life that is clicking and clacking away there.

To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause: The Many Lives of the Soviet Dissident Movement, Benjamin Nathans, 2024. Covered this podcast. A masterful book. For a taste:

Samizdat provided not just new things to read, but new modes of reading. There was binge reading: staying up all night pouring through a sheath of onion-skin papers because you’d been given twenty-four hours to consume a novel that Volodia was expecting the next day, and because, quite apart from Volodia’s expectations, you didn’t want that particular novel in your apartment for any longer than necessary. There was slow-motion reading: for the privilege of access to a samizdat text, you might be obliged to return not just the original but multiple copies to the lender. This meant reading while simultaneously pounding out a fresh version of the text on a typewriter, as a thick raft of onion-skin sheets alternating with carbon paper slowly wound its way around the platen, line by line, three, six, or as many as twelve deep. “Your shoulders would hurt like a lumberjack’s,” recalled one typist.

Experienced samizdat readers claimed to be able to tell how many layers had been between any given sheet and the typewriter’s ink ribbon. There was group reading: for texts whose supply could not keep up with demand, friends would gather and form an assembly line around the kitchen table, passing each successive page from reader to reader, something impossible to do with a book. And there was site-specific reading: certain texts were simply too valuable, too fragile, or too dangerous to be lent out. To read Trotsky, you went to this person’s apartment; to read Orwell, to that person’s.

However and wherever it was read, samizdat delivered the added frisson of the forbidden. Its shabby appearance—frayed edges, wrinkles, ink smudges, and traces of human sweat—only accentuated its authenticity. Samizdat turned reading into an act of transgression. Having liberated themselves from the Aesopian language of writers who continued to struggle with internal and external censors, samizdat readers could imagine themselves belonging to the world’s edgiest and most secretive book club. Who were the other members, and who had held the very same onion-skin sheets that you were now holding? How many retypings separated you from the author?

To Run the World: The Kremlin’s Cold War Bid for Global Power, Sergey Radchenko, 2024. Covered in a two-parter.

A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, George Saunders, 2021. Saunders reprints his favorite classic Russian short stories paired with essays on what each of them illustrate about the writing fiction. I can read much more deeply now thanks to the perspective this book brings. The audiobook featured all-star narration.

Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, Dan Wang, 2025. Covered in a pod with Dan here.

Past Years Best Books

H1 2025.

2024 (+ media diet)

and 2016…

Other H2 2025 books

The British Are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775-1777, Rick Atkinson, 2019. I respect Atkinson for the work he put in here but he’s just not on Ian Toll or Bruce Catton war trilogy level. It’s partially a skill issue but also just downstream of the material he’s working with—The Revolutionary War doesn’t have the source material, scale or sense of modernity to give historians as much to work with.

Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Joan Didion, 1968. Was Joan Didion built up too much for me to appreciate her? Like she’s good, but not world historic amazing. I loved this though. California is “out in the golden land, where every day the world is born anew. The future always looks good in the golden land, because no-one remembers the past. Here is the last stop for those who came from somewhere else, for all those who drifted away from the cold, and the past, and the old ways.”

The Secret of Our Success: How Culture Is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter, Joseph Henrich, 2015.

The Kill Chain: Defending America in the Future of High-Tech Warfare, Christian Brose, 2020. Covered on this pod.

Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s, Frederick Lewis Allen, 1931. The Scholar’s Stage did a great job summarizing this book here.

The Sword of Freedom: Israel, Mossad, and the Secret War, Yossi Cohen, 2025.

Part spy memoir, part political manifesto, incredibly ego-forward in a deeply Israeli way (him bragging about beating Pompeo at a shooting contest at the farm is really something). Interesting seeing someone who wanted to scream to the rooftops about how noble and professional his work is for so long finally getting the chance to do so. Best read in parallel with Rise and Kill First, a journalist’s take on the mossad.

The Forever War, Joe Haldeman, 1974. One interesting idea (literally brainwashing soldiers to do war crimes) surrounded by awful writing, awful characters, and blah sci fi. How is this a classic?

Attack and Die: Civil War Military Tactics and the Southern Heritage, Grady McWhiney and Perry D. Jamieson, 1982. An interesting thesis (Celtic heritage meant Southern officers and soldiers were way too into the offensive) they wait until the conclusion to lay out and don’t really prove, though tactical recklessness was clearly an issue.

War, Bob Woodward, 2024.

The Mission: The CIA in the 21st Century, Tim Weiner, 2025.

U. S. Grant and the American Military Tradition, Bruce Catton, 1954.

The Murderous History of Bible Translations: Power, Conflict and the Quest for Meaning, Harry Freedman, 2016. Great premise but really disappointed, should have picked fewer examples and gone deeper with more textual analysis.

I vote for compare and contrast, countries…

Thanks for this! I vote for corruption in China and the Potomac Army first:-)